Validation

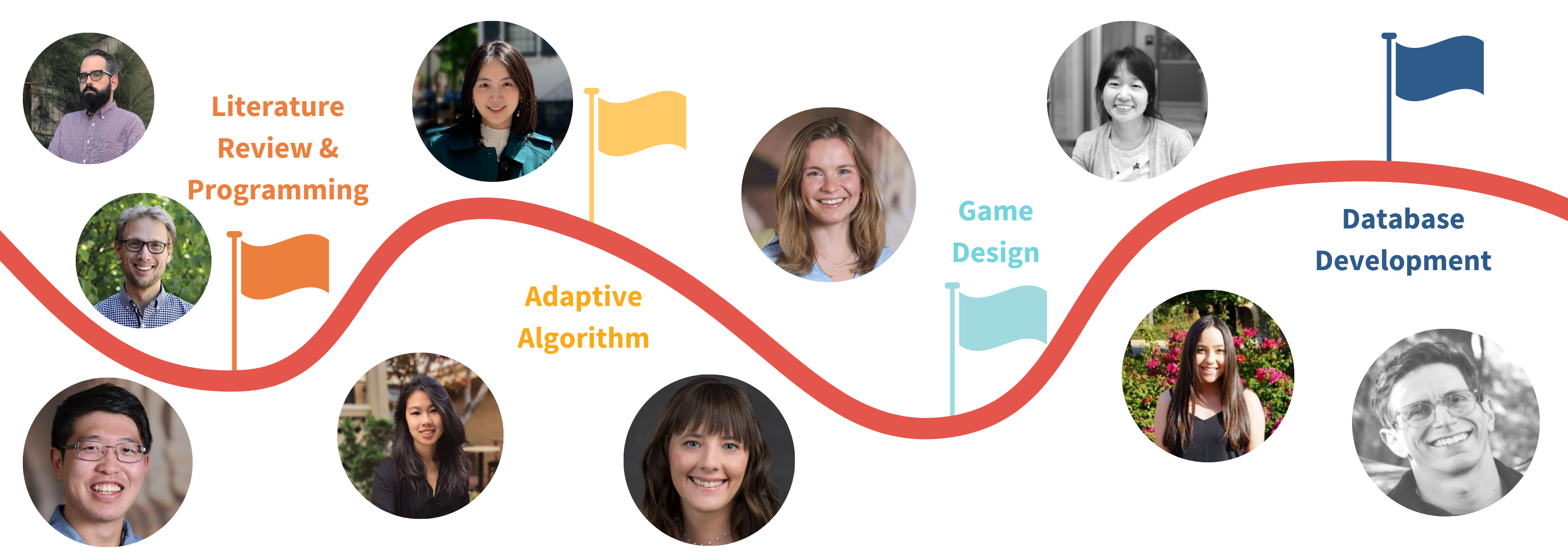

The Development of ROAR

We rely on data that we collect in both our lab and in schools to inform the best-practice uses and interpretations of the ROAR scores. To learn more about some recent research conducted to validate the ROAR, click on the tabs below to learn more about each study. Check back for updates to this page.

The ROAR was conceived in March 2020 – during the first shelter-in-place. The Brain Development & Education Lab and the Stanford University Reading & Dyslexia Research Program endeavored to create a tool that would allow reading research research to continue throughout the roller coaster of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our goal was to develop an accurate, reliable, expedient and automated measure of single word reading ability that could be delivered through a web-browser. Specifically, we sought to design a simple game in the web-browser that would approximate scores on the Woodcock-Johnson Basic Reading Skills Index 37. The Woodcock Johnson is one of the most widely used standardized measures of reading ability in research (and practice). Like other test batteries that contain tests of single word reading ability (e.g., The NIH Toolbox38, Wide Range Achievement Test39, Wechsler Individual Achievement Test40), the Woodcock Johnson Word Identification and Word Attack sub-tests require that an experimenter or clinician present each participant with single printed words for them to read out loud. Participant responses are manually scored by the test administrator as correct or incorrect based on accepted rules of pronunciation. The words are organized in increasing difficulty such that the number of words that a participant correctly reads is also a measure of the difficulty of words that the participant can read. Due to excellent psychometric properties, and widely accepted validity, the Woodcock-Johnson and a compendium of similar tests are at the foundation of thousands of scientific studies of reading development. Unfortunately, tests like the Woodcock-Johnson are not yet amenable to automated administration through the web-browser because speech recognition algorithms are still imperfect, particularly for children pronouncing decontextualized words and pseudowords.

In considering a suitable task for a self-administered, browser-based measure of reading ability, the lexical decision task is a good candidate for practical reasons. Unlike naming or reading aloud, lexical decisions can be: (a) scored automatically without reliance on (still imperfect) speech recognition algorithms, (b) completed in group (or public) settings such as a classroom and (c) administered quickly as each response only takes, at most, 1–2 s. The LDT has a rich history in the cognitive science literature as means to probe the cognitive processes underlying visual word recognition. It is broadly assumed that some of the same underlying cognitive processes are at play when participants make a decision during a two-alternative forced choice lexical decision as during other word recognition tasks (e.g. naming41,42). However, there are also major differences between the processes at play during a lexical decision versus natural reading43,44. For example reading aloud requires mapping orthography to a phonetic and motor outputs with many possible pronunciations (as opposed to just two alternatives in an LDT). Moreover, selection of the correct phoneme sequence to pronounce a word, or even the direct mapping from orthography to meaning (as is posited in some models45), certainly does not require an explicit judgement of lexicality. Thus, from a theoretical standpoint there was reason to be optimistic that carefully selected stimuli would tap into the key mechanisms that are measured by other, validated measures of reading ability (e.g., the Woodcock Johnson). However, concerns about face validity needed to be dispelled through extensive validation against standardized measures since there are also clear differences between lexical decisions and reading aloud.

In our first validation study we recruited 45 research subjects who had recently participated in studies in the Brain Development & Education Lab prior to the shelter-in-place. These participants had completed an extensive, in person reading assessment including measures such as the Woodcock Johnson. In this initial, proof of concept study we found a correlation of r = 0.91 between in person administration of the Woodcock Johnson and, un-proctored, at home completion of the ROAR.

The goal of our next validation study was to use item response theory to optimize the word/pseudowords in the ROAR for efficiency and reliability across a broad range of reading abilities. Specifically, we wanted 3, “short form” tests that are”:

- Efficient: About 3 minutes to administer

- Reliable: At least r=0.90 test-retest reliability (equivalent to other standardized reading assessments)

- Valid for a broad ability range: Spanning dyslexic to exceptional readers from from first grade through high-school

- Multiple test forms: Matched in terms of difficulty for repeated administration

We recruited 120 participants between 7 and 25 years of age, used these data to calibrate item response theory models, and created three, optimized word lists that were matched on difficulty, spanned a broad age range, and could be administered in under 5 minutes. The figure below shows the test-retest reliability of each test form and the correlation between performance on each ROAR test form and scores on the Woodcock Johnson.

The optimized test forms from Study 2 had good psychometric properties starting around 2nd grade. To make the test applicable to first graders (and English Language Learners) we selected easy vocabulary words from 1st grade leveled texts. These new stimuli were added to each ROAR test form and the instructions and practice blocks were animated and recorded by a professional voice actor to make the ROAR engaging for younger children. Then another validation study was run in N=24, 6 and 7 year olds to investigate whether young children could follow instructions and provide accurate data on a self-administered online assessment.

Next, in a study with N=131 participants ages 6-41 years, we confirmed that performance was matched across the three word lists used in the different test forms (lists A, B, C) and that performance didn’t change as depending on the order of the lists.

We ran a final validation study with N-101 participants where we validated the optimized version of the ROAR in a broad age range spanning ages 6 through 40. Each participant completed the ROAR on their personal computer at home and then participated in a reading assessment session over Zoom where they were administered the Woodcock Johnson and other tests. The validation data was consistent with the previous validation studies: the ROAR was highly reliable and correlated at r=0.90 with performance on the Woodcock Johnson.