| Proportion correct | |

|---|---|

| V | 0.84 |

| B | 0.85 |

| E | 0.85 |

| H | 0.85 |

| K | 0.85 |

| G | 0.86 |

| P | 0.86 |

| I | 0.87 |

| L | 0.87 |

| N | 0.87 |

| T | 0.87 |

| D | 0.88 |

| J | 0.88 |

| R | 0.88 |

| U | 0.88 |

| C | 0.89 |

| F | 0.89 |

| M | 0.89 |

| Q | 0.89 |

| S | 0.89 |

| Y | 0.89 |

| Z | 0.90 |

| W | 0.91 |

| A | 0.92 |

| O | 0.92 |

| X | 0.92 |

10 ROAR Dyslexia Screening and Subtyping

Beyond measures of reading skills, many state dyslexia screening initiatives require additional predictors of dyslexia. Dyslexia is defined in terms of reading skills (Maggie Snowling and Hulme 2024; O’Brien and Yeatman 2021; Catts et al. 2024; Lyon, Shaywitz, and Shaywitz 2003; Fletcher et al. 2006; Elliott and Grigorenko 2024), but there are two reasons why additional predictors are useful:

- Improved prediction accuracy: Even though dyslexia is defined in terms of reading skills, that does not mean dyslexia begins in school. There are a collection of (potentially but not necessarily causal) factors that can be measured prior to formal reading instruction that predict future risk for dyslexia. There are also skills that can be measured at the earliest stages of reading instruction that are useful for prediction and early risk assessment. Thus, from a practical standpoint, including early predictors of dyslexia in a screener improves sensitivity and specificity (irrespective of the causal relationship between the predictors and reading development).

- Dyslexia subtyping and individualized intervention: Dyslexia research has embraced multifactorial models where dyslexia is considered a probabilistic outcome that emerges from the combined influence of a collection of risk factors and protective factors (O’Brien and Yeatman 2021; Catts et al. 2024, 2024; B. F. Pennington 2006; Compton 2021; Zuk et al. 2021; van Bergen, van der Leij, and de Jong 2014; Wolf and Bowers 1999). Even though phonological awareness (PA) is still considered one of the most important mechanisms underlying dyslexia (Margaret Snowling 1998; M. J. Snowling, Hulme, and Nation 2020; Wagner and Torgesen 1987; Stanovich 1998), the field of dyslexia research has broadly reached consensus that a collection of mechanisms beyond difficulties with PA confer risk for dyslexia. This new understanding of dyslexia embraces heterogeneity: not every student’s struggles are the same and knowing the root of a student’s struggles could help plan the most efficacious intervention. However, currently, the notion of personalized intervention for particular dyslexia subtypes is more of an aspiration than a reality. One of the challenges is that the measures that are useful for phenotyping are not necessarily the most effective intervention targets. For example measures of Rapid Automatized Naming (RAN) and Rapid Visual Processing are prime examples: even though a wealth of research has established that these measures are useful for prediction, and can identify different profiles of struggling readers, it has not been established how intervention should differ based on these profiles.

We organize the ROAR Dyslexia Screening and Subtyping battery into screening measures that target:

- Foundational Reading Skills that indicate dyslexia Section 10.1 and are established intervention targets

- Dyslexia Prediction and Subtyping which includes measures of various mechanisms that are hypothesized to be causally related to dyslexia, improve screening sensitivity and specificity, but aren’t established intervention targets Section 10.2.

ROAR has been validated as a dyslexia screener beginning in the Spring of kindergarten. Many of the individual measures are valid earlier (as young as 4 years of age (Gijbels, Burkhardt, and Ma 2024)), but validation of ROAR dyslexia screening measures in the Fall of kindergarten is ongoing.

10.1 Dyslexia screening based on foundational reading skills

People with dyslexia struggle learning how to read. The most direct way to screen for difficulties consistent with dyslexia is to use measures of foundational reading skills, which is why these skills are included in the ROAR Foundational Reading Skills Suite. Children with dyslexia are delayed relative to their peers in the development of: (1) Phonological Awareness (PA; see Chapter 7), (2) Letter Sound Knowledge (see Chapter 8), (3) real word and pseudo word reading (see Chapter 5), and (4) reading speed, efficiency or fluency (see Chapter 6). Difficulties with all these skills can persist through adulthood without proper identification and intervention. The goal of screening based on foundational reading skills is to a) identify challenges early in in elementary school and b) intervene while the developing brain is optimally plastic and interventions are most effective (Gaab and Petscher 2022; Blachman 2013; Torgesen 2004, 1998; Lovett et al. 2017). For example, Lovett et al. (2017) has shown that intervening early is more efficient (larger effects per hour of intervention) compared to waiting until later in elementary school. To quote Torgesen (1998), the goal of early screening is to “catch them before they fall”.

10.2 Dyslexia prediction and subtyping

Wolf and Bowers (1999) and colleagues first introduced the “double deficit hypothesis” as a response to the “core phonological deficit hypothesis” and demonstrated that a) some children with typical PA skills still struggle learning to read and b) many of these struggling readers have early challenges with Rapid Automatized Naming (RAN) (Denckla and Cutting 1999; Denckla and Rudel 1976; Wolf and Bowers 1999; Compton, DeFries, and Olson 2001; Wolf et al. 2002). Additionally, children who struggle with PA and RAN tend to have even larger challenges with reading than those who only struggle on one skill. RAN is now required by most dyslexia screening legislation. However, RAN is not a useful intervention target per se: whereas a child who struggles with PA will benefit from training targeting PA (Bradley L and Bryant P E 1983), a child struggling with RAN does not simply need to practice RAN. Each of the measures in the ROAR Foundational Reading Skills battery is a core component of reading development and a useful intervention target. Measures in the Dyslexia Prediction and Subtyping battery are predictive of reading development and often help to understand the mechanisms underlying a student’s struggles, but are not proven intervention targets. For example, RAN (see Section 10.2.1) is highly predictive of future reading development, and also indicates a different type of struggle than PA (i.e., automatization or connectivity between visual and verbal processing), but is not a skill that needs direct instruction. Rapid Visual Processing (see Section 10.2.2)is another measure that has mounting evidence of a causal relationship to reading development and has utility as a screener but is not a skill that should be directly taught (Ramamurthy, White, and Yeatman 2024a; Ramamurthy et al. 2024; Lobier and Valdois 2015; Marie Line Bosse, Tainturier, and Valdois 2007).

10.2.1 Rapid Automatized Naming (ROAR-RAN)

10.2.1.1 Structure of the task, administration and scoring

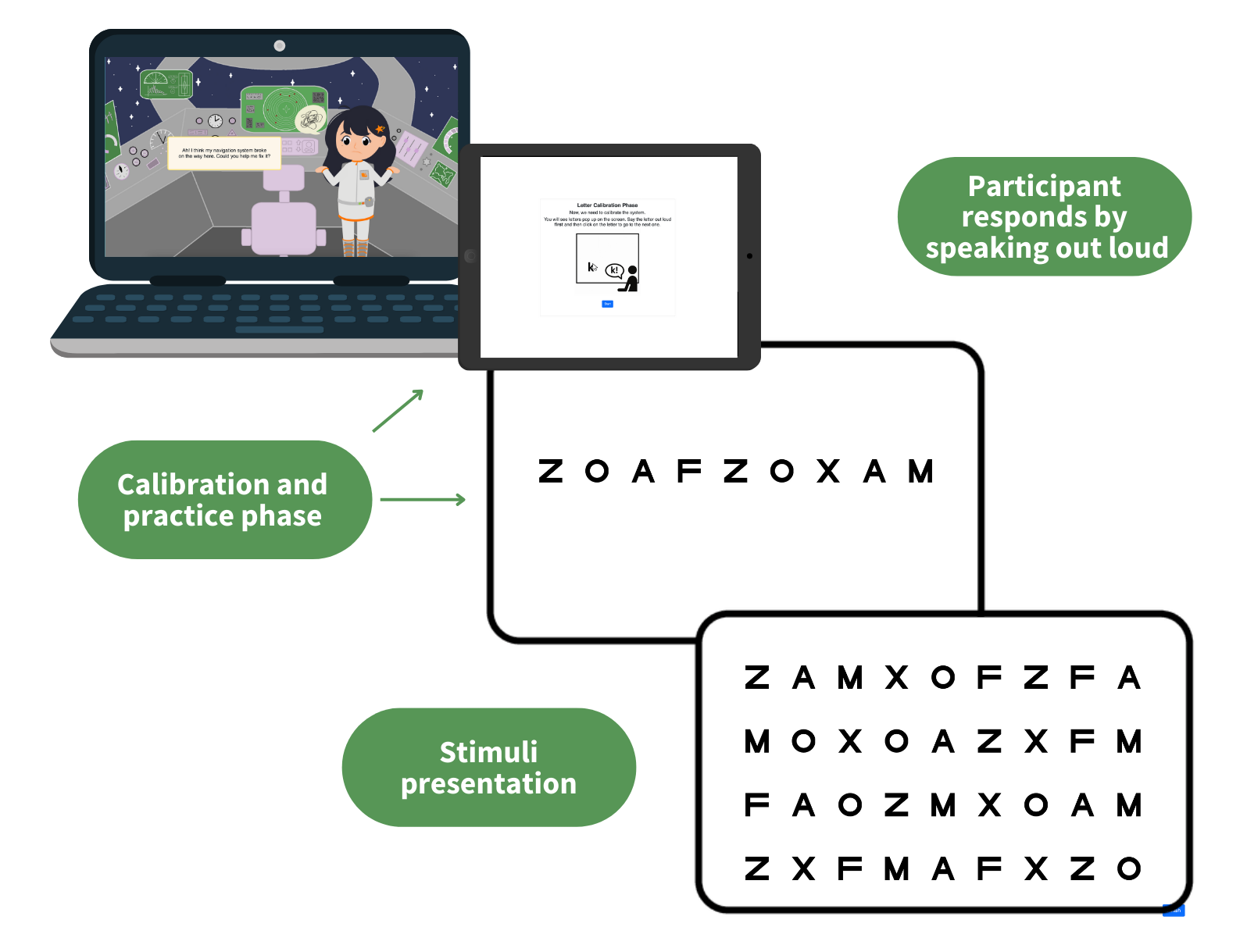

ROAR-RAN is the only ROAR measure that requires verbal responses. Thus, ROAR-RAN has unique considerations for administration and scoring. Whereas all other ROAR measures are specifically designed and validated to produce accurate and reliable results in a large group setting (e.g., a classroom) where dozens (or hundreds) of students are silently completing ROAR assessments at the same time, we recommend that students taking ROAR-RAN are provided a quiet and private space. Even though the automated scoring algorithm implemented in ROAR-RAN can filter out background noise and accurately score ROAR-RAN in a group administration setting, the distraction of hearing other, nearby students rapidly naming the RAN stimuli might affect the validity of scores. This concern is not specific to ROAR-RAN and will be an issue for any group-administered measure that requires verbal responses. This is not an issue for other ROAR assessments because all other ROAR assessments are completed silently, with student responses recorded via the keyboard, mouse, or swipe-modalities. RAN is specifically designed to measure naming speed. Since speed is the fundamental unit of the measure, and since naming must be done out loud, it is important that participants are in a space where they can speak rapidly and without distraction while taking ROAR-RAN. Figure 10.1 depicts ROAR-RAN.

Similar to other ROAR measures, RAN is scored automatically and instructions are narrated by characters in a game-like setting. RAN does not require a test administrator to administer or score the assessment, though young students might need some monitoring in order to stay focused on the task. Previous work has validated the use of a digitized, online version of RAN for dyslexia screening (Kim et al. 2024).

To prepare for ROAR-RAN, students should be in a private space where they can speak out loud without distractions. Akin to other ROAR measures, students log in to the dashboard and click to launch the ROAR-RAN assessment. Upon launch, a character will narrate the instructions. The participant will first be cued to name each individual item—letters, numbers or colors. This serves as a check to ensure that the participant knows the name of each item, and the interaction calibrates the automated scoring algorithm. After the quick calibration phase, the participant is then instructed to name all the items they are about to see in sequence as quickly as possible. A countdown indicates the beginning of the measure, the stimuli are presented, and the participant’s responses are recorded through the microphone. The webcam is also used to track the participant’s gaze so that the speech data can be co-registered to the item the participant is fixating, allowing for more precise scoring of individual items.

Scoring is performed automatically by the ROAR-RAN automated scoring algorithm. The algorithm processes the speech data and records the timestamp and duration for each spoken item, measuring both the speed and accuracy of the participant’s responses. If a participant incorrectly identifies more than three items, the test is invalidated. For valid tests, the system calculates the total time taken to complete the task by recording the timestamp of the participant’s response to the first symbol and the timestamp of their response to the last symbol. This total duration, measured in seconds, is then reported as the participant’s score on the ROAR-RAN assessment (see Section 20.1 for validation of the scoring algorithm).

Since RAN is fundamentally about naming, it is the only ROAR assessment that requires a webcam. Responses are recorded, securely stored, scored with an algorithm, and scores are displayed in the ROAR score report.

10.2.1.2 RAN-Letters

RAN is intended to measure naming that is “automatized”. To select the ideal upper case letters for RAN-Letters we assessed knowledge of upper case letter names in 4,022 kindergarten and first grade students and calculated the proportion of students that knew the name of each upper case letter name (see Table 10.1). For the RAN-Letter stimuli, we chose the 6 monosyllabic letter names with a) the highest accuracy and b) phonetically distinct: X, A, O, Z, F, M

10.2.1.3 RAN-Colors

For young children who have not yet established sufficient letter knowledge for RAN-Letters, RAN-Colors is more appropriate. In RAN-Colors, rather than upper case letters, the stimuli are an array of color patches. The task is the same: the participant sequentially names all the colors as quickly and accurately as possible. RAN-Colors uses the following colors which have distinct and unambiguous names: Red, Blue, Pink, Black, Yellow. RAN-Colors does not use Green due to the high occurance of Red/Green color blindness.

10.2.1.4 RAN-Numbers

Another option for young children who have not yet established knowledge of letter names is RAN-Numbers. The following numbers are used as stimuli in RAN-Numbers: 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8.

10.2.2 Rapid Visual Processing

10.2.2.1 Theoretical background

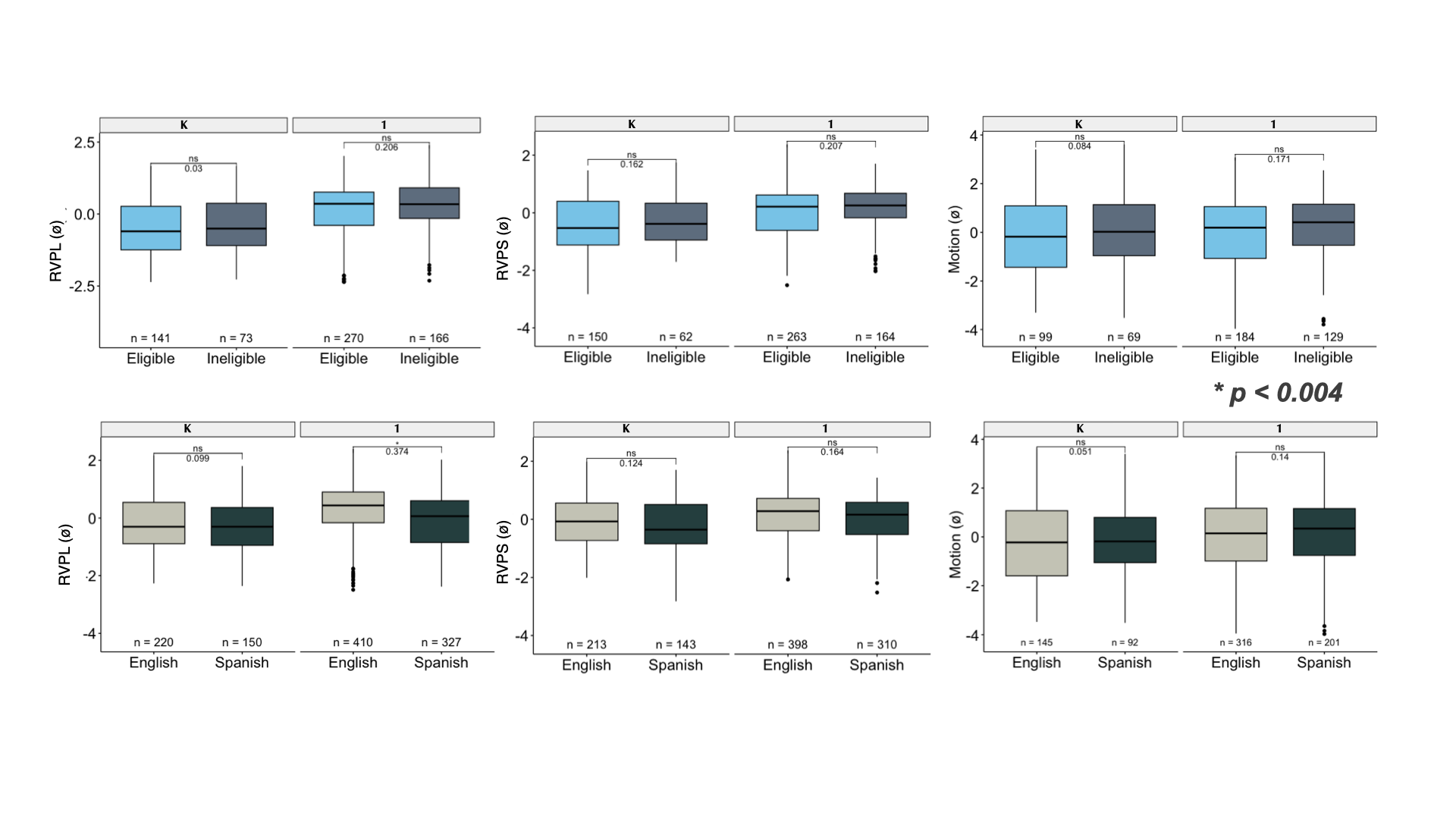

There is a long-standing controversy about the visual factors associated with dyslexia. While phonological difficulties have been widely recognized as a core feature of dyslexia, debate has persisted over visual processing theories, suggesting a more complex, multifaceted etiology (R. Pennington and Pennington 2011; Vellutino, Fletcher, and Snowling 2004; O’Brien and Yeatman 2021). The field has yet to reach consensus because existing theory on visual processing differences in dyslexia is often built upon small samples, using experimental measures without established psychometric properties, that are deployed across different age ranges often without prior work demonstrating the validity of the measure in each developmental window. Validated measures of visual processing that predict future reading development could contribute in overcoming the challenges faced by other screening measures since visual development is language-agnostic and not directly taught in preschool.

Rapid Visual Processing (RVP) refers to the ability to rapidly encode and recall multiple visual elements simultaneously in a brief glimpse (Sperling 1960, 1983). In this task, a string of letters or symbols is briefly flashed at the center of the screen and then the participant is cued to report the identity of a single randomly chosen element. Of all the measures of sensory processing that have been studied in relation to word reading difficulties, the rapid visual processing task has the strongest evidence for identifying a subgroup of struggling readers who are not captured by conventional measures of phonological awareness. Previous studies have demonstrated that this task:

- Consistently correlates with reading ability (Marie-Line Bosse and Valdois 2009; Ramamurthy, White, and Yeatman 2024b).

- Differs in children with dyslexia (Lobier, Zoubrinetzky, and Valdois 2012; Ramamurthy, White, and Yeatman 2024b).

- Cannot be explained as a consequence of dyslexia (Lobier and Valdois 2015).

- Might be a useful intervention target (Valdois et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2019; Zoubrinetzky et al. 2019).

- Identifies a subset of poor readers that have high phonological awareness despite their reading difficulties (Saksida et al. 2016; Valdois, Reilhac, and Ginestet 2020).

- Recent evidence suggests that the difficulties with Rapid Visual Processing in children with dyslexia are consistent across languages including French, English, Dutch and Chinese (Huang, Liu, and Zhao 2021; Lobier and Valdois 2015) making this an ecologically relevant measure related to reading across different languages.

By including both letter and symbol stimuli, the task allows for the assessment of rapid visual processing skills both within and independent of language experience. The measure’s language-agnostic nature makes it particularly valuable for early screening, as visual processing issues precede reading difficulties. This approach, of including visual measures that are linked to reading, aligns with emerging multifactorial models of dyslexia, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the various cognitive factors influencing reading development (O’Brien and Yeatman 2021; Catts et al. 2024; B. F. Pennington 2006; Compton 2021; Zuk et al. 2021; van Bergen, van der Leij, and de Jong 2014; Wolf and Bowers 1999).

10.2.2.2 Structure of the task

The Rapid Visual Processing Task was developed in close collaboration with the UCSF Multitudes project. Task design, data collection and analysis was shared across the two projects.

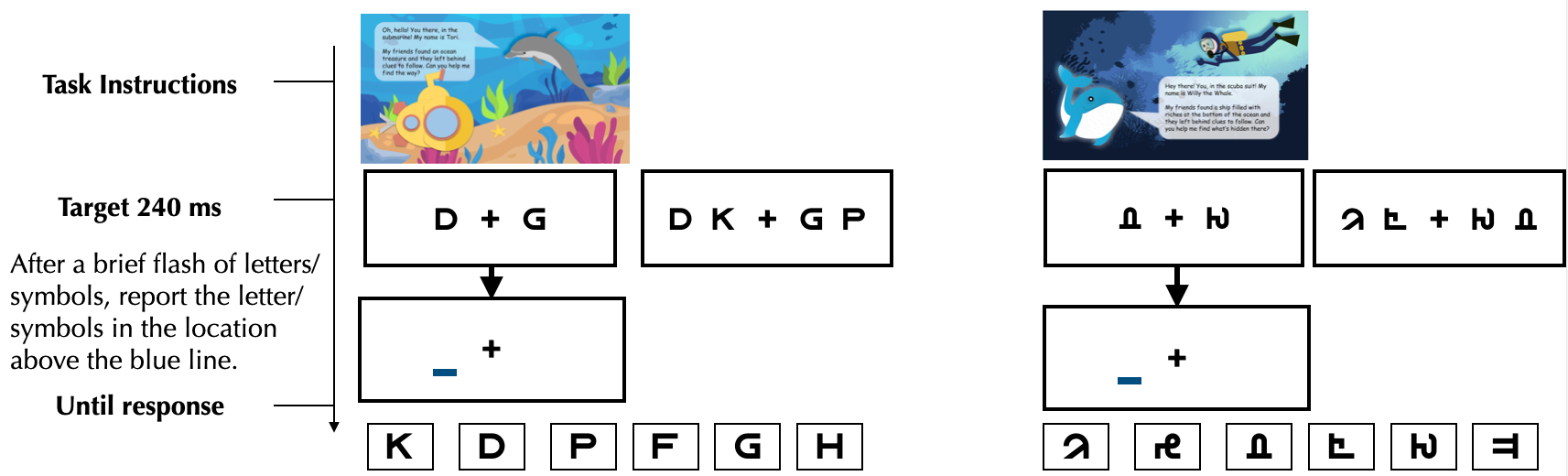

ROAR-RVP has 2 versions that measure the same construct of rapid visual processing: Rapid Visual Processing with Letters (RVPL) and Rapid Visual Processing with Symbols (RVPS). RVPL measures the ability to rapidly locate and identify letters in 2-, 4-, and 6-letter strings. RVPS assesses the ability to rapidly locate and identify non-namable visual symbols, making it language-agnostic. These tasks are considered promising tools for early identifying of struggling readers not captured by conventional phonological awareness measures.

- Letters (RVPL)

- Symbols (RVPS)

ROAR-RVP employs a six-alternative forced choice task presented as an engaging underwater adventure game. There are two versions, each with two difficulty blocks (2- and 4- element strings. 6-element string can be added for older students). Participants help a lost dolphin (RVPL) or whale (RVPS) find friends and treasures. The task sequence involves fixating on a central point where 2-4 elements (letters or pseudo-letters) briefly appear (240ms). A post-cue then indicates the target position, and participants select the correct element from six choices. Each version begins with 6 longer-duration practice items. Narrated instructions, encouragement animations, and feedback sounds guide participants throughout. The game is designed for K-2 children but can be extended to older students and adults.

Figure 10.2 shows the rapid visual processing task with letters (RVPL) a string of letters is briefly flashed at the center of the screen (240ms) and then the participant is cued to report the identity of a single randomly chosen letter. The participant’s task is to report the identity of the target element that was at the prompted single location, by tapping on one letter from a set of 6 letter choices provided. This task was optimized to provide highly reliable metrics of rapid visual processing in children as young as five years of age (see Section 20.2)