7 Phonological Awareness (ROAR-Phoneme)

Phonological awareness (PA), or phonological processing more broadly, refers to a metalinguistic skill that enables an individual to reflect upon and manipulate the sound structure of spoken language (Tunmer, Herriman, and Nesdale 1988), at the level of (1) words and syllables, (2) onsets and rimes, or (3) phonemes independent of their meaning (Stanovich 2017; Treiman and Zukowski 1991). PA skills emerge early, develop rapidly throughout childhood (Nittrouer, Studdert-Kennedy, and McGowan 1989), and have important implications for literacy achievement (Moyle, Heilmann, and Berman 2013). To learn how to read, a child needs to be aware of the arbitrary and conventional correspondence between the sound structure of language and the rules for how it is written (Anthony and Francis 2005). Thus, measures of PA are an important indicator of early reading development and are one of the most established measures in dyslexia screening. ROAR-Phoneme was developed and validated as an efficient, precise and automated measure of PA that does not depend on verbal responses (Gijbels, Burkhardt, and Ma 2024). Gijbels, Burkhardt, and Ma (2024) provide a detailed account of the research, development and validation process, and we lay out the pertinent technical details here.

7.1 Structure of the task

ROAR-Phoneme has 3 sub-tests that measure different dimensions of phonological awareness:

- First-Sound Matching (FSM)

- Last-Sound Matching (LSM)

- Deletion (DEL)

And two optional sub-test that were deemed unnecessary for obtaining a reliable and valid measure of PA but still have utility in specific use cases (for more information see (Gijbels, Burkhardt, and Ma 2024)):

- Blending (BLE)

- Rhyming (RHY)

ROAR-Phoneme employs a one-interval, three-alternative forced choice task. Instructions are narrated by a character, and the participant selects the appropriate response with a touchscreen or mouse click. ROAR-Phoneme consists of 3 subtests (19 items per subtest), with each subtest consisting of 2 or 3 blocks (divided by difficulty level). Each subtest starts off with 3 training items with feedback. Training items have to be completed correctly before the task will continue to the test items. To engage children from pre-k through 5th grade, the task is embedded in a story where the child has to help a monkey and his friends (rabbit, bear, and otter) collect their favorite foods. At the end of every trial, images of food are displayed. At the end of every block, a visualization of the collected food is presented, and the character provides encouragement (e.g., “Great job! So many bananas! Let’s get a few more!”). Every character provides the instructions of their own subtest, guides throughout the task, motivates the participants to take short breaks between blocks, and introduces their next friend.

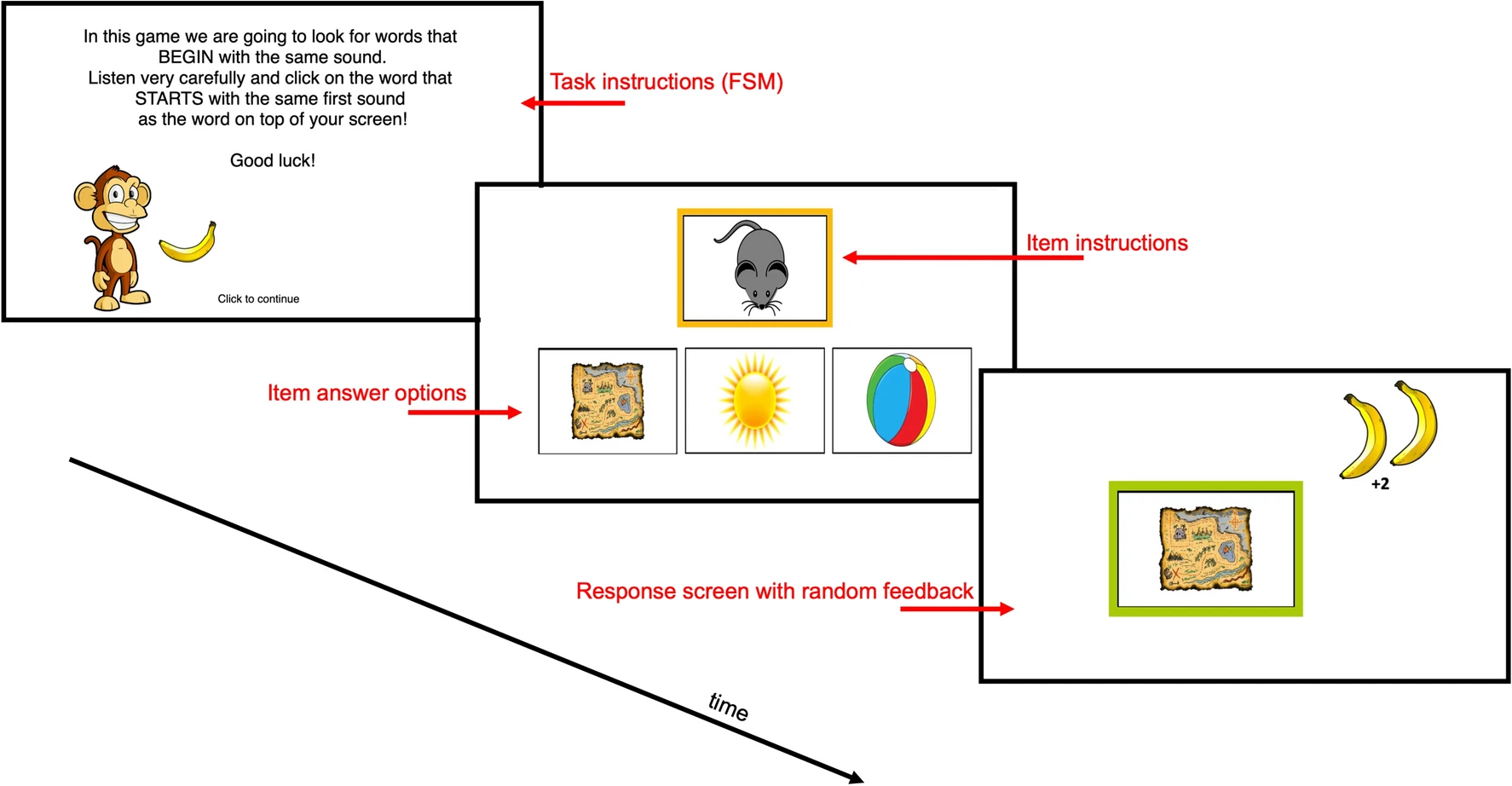

Participants are instructed to work on a computer or tablet sitting at a desk. Sound has to be turned on and set to a comfortable level, based on the instructions of one of the characters. All game instructions are provided in both text and audio. For all trials of all subtests, one image, accompanied by an audio fragment, recorded by a First-language English-speaker, provides the specific instruction of that trial (e.g., subtest FSM: “Which picture starts with the same sound as dog?”). This screen shown in Figure 7.1 is followed by the instruction image (top) plus three answer options (left, middle, right). All images are verbalized (e.g., “dam” (target), “goat” (foil 1), “mop” (foil 2)) and the position of the images is randomized for each trial. For the DEL subtest, the images are not verbalized as this could give away the correct answer. In contrast, participants are allowed to listen to the instruction phrase two times for this subtest. We did not implement the ability to listen to the instructions more than once throughout the entire task to stay as consistent as possible with standardized PA tasks like the CTOPP-2 in which instructions are not repeated. Participants pick a response by clicking the image, which is followed by a visualization of the response with a random number of food images as motivation (Figure 7.1).

7.2 Scoring

ROAR-Phoneme is a three alternative forced choice (3AFC) task and items are scored as correct or incorrect (dichotomous scoring) by comparing the participant’s response (touchscreen/click selection), to the true classification (real/pseudo) of the item. Each response is scored in real time. The participant’s ability or scaled score (\(\theta\)) on ROAR-Phoneme is computed based on an item response theory (IRT) model. IRT puts ability (\(\theta\)) on an interval scale meaning that scores on ROAR-Phoneme can be compared over time and across grades.

Types of Scores

- Raw Scores: ROAR-Phoneme raw scores are the number (or proportion) of items that a participant gets correct. We recommend using Scaled Scores rather than raw scores.

- Scaled Scores: ROAR-Phoneme scaled scores are computed based on an IRT model which puts ability (\(\theta\)) on an interval scale. Scaled scores are then put on a scale spanning 100-900 by applying a linear transform to \(\theta\) estimates. \(\text{ROAR Score} = \text{round}\left( \left( \frac{\theta + 6}{3} \times 200 \right) + 100 \right)\)

- Percentile Scores: Percentile scores are computed in 2 ways (see Chapter 3):

- Based on ROAR Norms

- Based on linking ROAR-Phoneme scores to Standard Scores on the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) (Wagner, Torgesen, and Rashotte 1999). This linking allows ROAR-Phoneme scores to be interpreted with direct reference to the criterion measure that is often used to define dyslexia risk (see Gijbels, Burkhardt, and Ma (2024) for more information on the linking model).

- Standard Scores: Age standardized scores for ROAR-Phoneme put scores for each age bin on a standard scale (normal distribution, \(\mu=100\), \(\sigma=15\)) and are computed in 2 ways:

- Based on ROAR Norms

- Based on linking ROAR-Phoneme scores to CTOPP Standard Scores.