5 Single Word Reading (ROAR-Word)

ROAR-Word uses a lexical decision task to measure single word reading ability. Rapid and automatic word recognition is a foundation of most theories of reading ability (Ehri 2005; Perfetti 1985), and a two alternative forced choice (2AFC) lexical decision task (LDT) has a rich history in the cognitive science literature as a means to probe the processes underlying word recognition. Decades of theory and data have demonstrated that lexical decisions and reading out loud tap into many of the same underlying cognitive processes (Seidenberg and McClelland 1989; Balota, Yap, and Cortese 2006; Katz et al. 2012; Keuleers, Lacey, and Rastle 2012). While reading out loud is often considered the “gold standard” methodology for assessing single word reading ability, there is no theoretical reason to prefer a verbal versus a silent response. The goal of a single word reading assessment is to measure the complexity of words that can be accurately read and silent reading, not reading out loud, is the ultimate goal. Reading out loud has an easily observable response so is the focus of many assessments of single word reading. But reading out loud also has the drawback of requiring knowledge to be accurately mapped to a very specific motor output which can be a barrier for children with speech impediments as well as for those who speak with accents or language variants that are not reflected in the scoring criteria of the assessment (Brown et al. 2015; Washington and Seidenberg 2021). These issues with language variation also allow potential bias of the administrator to affect the scoring of the assessment: many standardized assessments consider language variants as errors (Washington and Seidenberg 2021). Moreover, reading out loud has the practical drawback of not being amenable to group administration, requiring manual scoring, and often having subjective scoring criteria. For all of these reasons, we designed ROAR-Word as a silent, lexical decision task to avoid the bias and barriers to scale that can be inherent in measures that are scored based on reading out loud. The item bank was designed based on the extensive cognitive science literature on lexical decisions such that items systematically sample different theoretically important dimensions of lexical and orthographic properties (see Yeatman et al. 2021; Ma et al. 2023 for more a more detailed description of the item bank).

In addition to the theoretical reasons why a properly designed lexical decision task can serve as a valid index of single word reading ability, there is also broad empirical support. For example (Van Bon, Hoevenaars, and Jongeneelen 2004) compared a pencil and paper lexical decision task to a standardized, single word reading aloud measure and found strong correlations between the silent and oral reading measures. (Van Bon, Tooren, and van Eekelen 2000) even found that lexical decisions predicted reading out loud at the item level. Commercially available assessments, such as the CAPTI from ETS, also rely on a modified LDT as a measure of “word recognition and decoding” (Sabatini et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019). Sabatini et al. (2019) present a strong case for face validity, and report that this measure is distinct from vocabulary and comprehension. In creating ROAR-Word, we a) designed an item bank grounded in the cognitive science of reading development, b) used item response theory (IRT) to calibrate an efficient and highly reliable unidimensional Rasch measurement scale, and c) undertook a series of studies to demonstrate excellent convergent validity with standardized, individually administered measures of single word reading (Yeatman et al. 2021; Ma et al. 2023; Barrington et al. 2023).

5.1 Structure of the task

Figure 5.1 shows the structure of the ROAR-Word task. ROAR-Word is a computer adaptive test (CAT) with 84 items that are sampled from a large item bank (>600 items). ROAR-Word begins with instructions that are narrated by characters that introduce the task as a fun adventure. Instructions are followed by practice trials with feedback to ensure that the participant understands the goal of the lexical decision task and how to respond to real and nonsense words. Finally, after practice trials, the participant is presented with 84 CAT items divided across three blocks with breaks in between each block. Throughout the task, participants are rewarded by gold coins and new characters along their journey which helps with focus and engagement.

For each task trial a real or pseudo word is presented for 350ms and the participant is cued to indicate with a keypress, touchscreen or swipe whether the word was real or made up. The participant can take as long as needed to respond.

5.2 Design and validation of items

The ROAR-Word measurement scale has already been validated in previous publications (Yeatman et al. 2021; Ma et al. 2023; Barrington et al. 2023). Each individual item is validated based on its fit to the IRT measurement scale. ROAR-Word uses a Rasch (one parameter logistic) model (with a guess rate of 0.5) and item fit is assessed based on infit and outfit statistics using standard criteria (Wu and Adams 2013). Items are included in the assessment if infit and outfit are between 0.7 and 1.3.

Additionally, item parameters are validated to ensure that items function similarly across diverse demographic groups. Ma et al. (2023) report an analysis of parameter invariance across four groups of school districts that differ dramatically in terms of:

- Race/Ethnicity

- Percentage of English language learners

- Median income

- Percentage of students who qualify for free and reduced price lunch

Ma et al. (2023) demonstrated that after removing a small number of items, item difficulty was consistent across all the school districts included in the sample.

5.3 Scoring

ROAR-Word is a two alternative forced choice (2AFC) task and items are scored as correct or incorrect (dichotomous scoring) by comparing the participant’s response (keypress/touchscreen/swipe indicating real word vs. pseudo word), to the true classification (real/pseudo) of the item. Each response is scored in real time. The participant’s ability or raw score (\(\theta\)) on ROAR-Word is computed based on an item response theory (IRT) model. IRT puts ability (\(\theta\)) on an interval scale meaning that scores can be compared over time and across grades.

Types of Scores

- Scaled Scores: ROAR-Word Scaled Scores are computed based on an IRT model which puts ability (\(\theta\)) on an interval scale. Scaled Scores are then put on a scale spanning 100-900 by applying a linear transform to \(\theta\) estimates. \(\text{ROAR Score} = \text{round}\left( \left( \frac{\theta + 6}{3} \times 200 \right) + 100 \right)\)

- Percentile Scores: Percentile scores are computed in 2 ways (see Chapter 3):

- Based on ROAR Norms

- Based on linking ROAR scores to Woodcock Johnson Basic Reading Skills (WJ BRS) Standard Scores. This linking allows ROAR-Word scores to be interpreted with direct reference to the criterion measure that is often used to define dyslexia risk.

- Standard Scores: Age standardized scores for ROAR-Word put scores for each age bin on a standard scale (normal distribution, \(\mu=100\), \(\sigma=15\)) and are computed in 2 ways:

- Based on ROAR Norms

- Based on linking ROAR scores to WJ BRS Standard Scores.

5.4 Norms

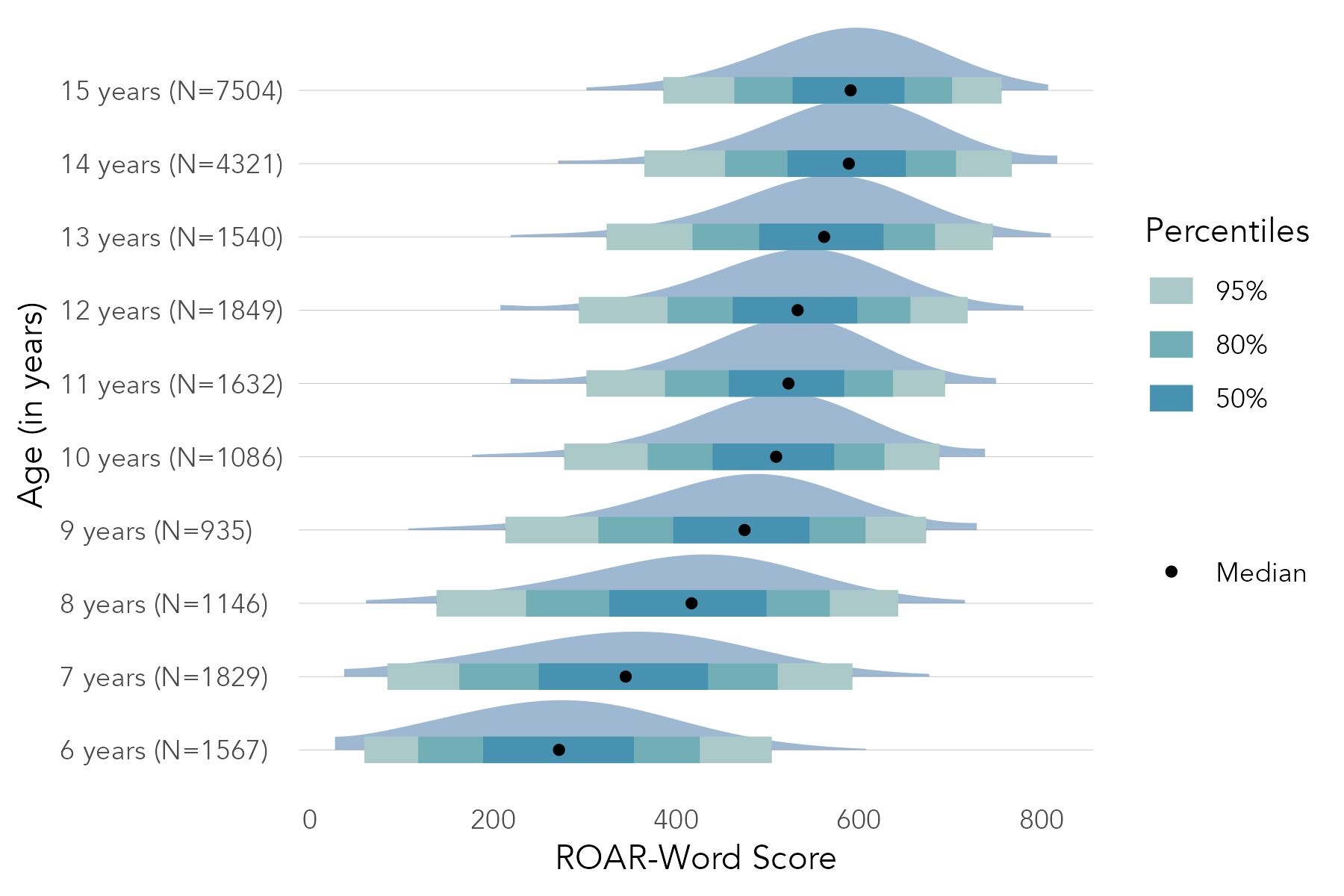

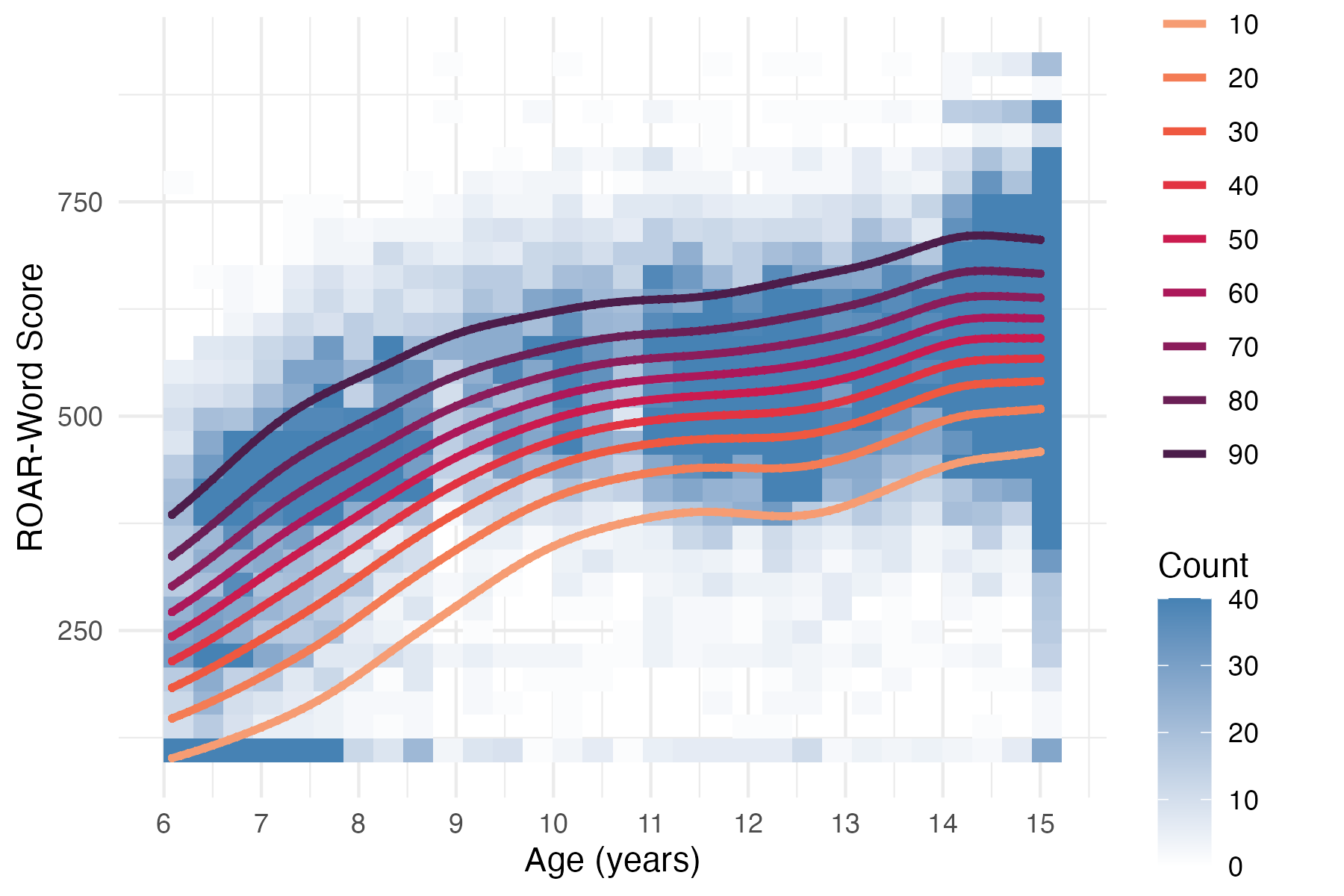

Section 3.4 describes the norming model used for ROAR-Word (and the Foundational Reading Skills Suite). Figure 5.2 shows the normative progression of ROAR-Word Scaled Scores as a function of age and Figure 5.3 shows percentile curves fit to ROAR-Word Scaled Scores.

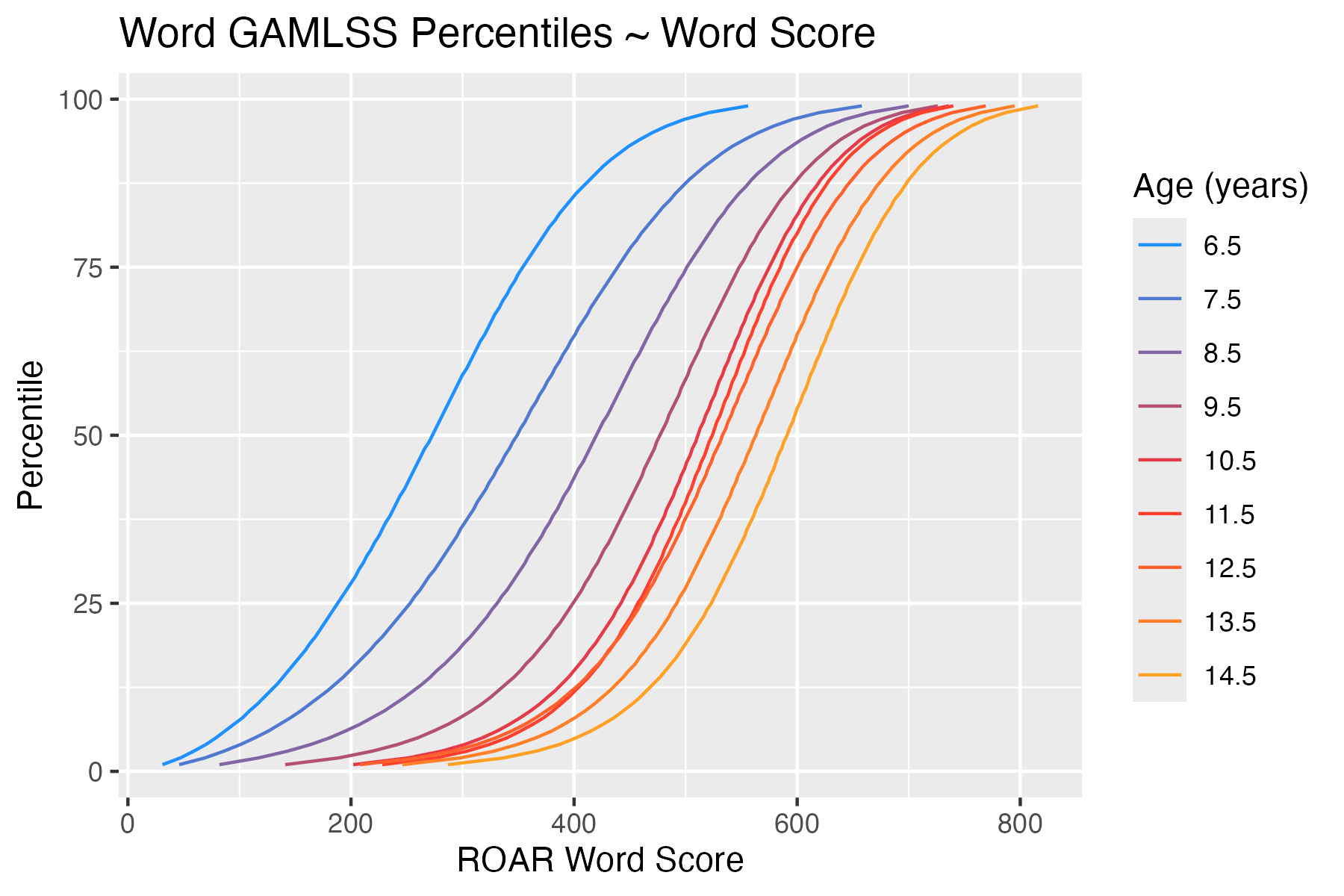

Based on this norming model, Percentile Scores are derived for each age. Figure 5.4 shows the relationship between ROAR-Word Scaled Scores and Percentile Scores.