11 Multilingualism

A widely accepted definition of multilingualism (often used interchangeably with the term bilingualism) describes “anyone who can communicate in more than one language, be it active (through speaking and writing) or passive (through listening and reading)” as multilingual (Wei 2008, 4). Moreover, multilingual individuals are a very heterogeneous group, with differences in, for example, the ages of acquisition (the age at which they learn their languages), proficiency levels in each of their languages, contexts of use (such as at home, school, or in work environments), and degree of balancedness between their languages (where some individuals are equally fluent in all their languages, while others may be stronger in one language over another). This, in turn, means that multilingualism is a very individual phenomenon (Blumenfeld, Bobb, and Marian 2016; Grosjean 2008).

Most importantly, multilingual individuals should not be viewed as “two monolinguals in one person” (Grosjean 1989, 4). This implies that their performance on a test measuring a given construct must not be interpreted using monolingual norms in either of their languages without appropriate considerations and qualifications. While performing at or above monolingual norms might indicate the absence of reading difficulties Section 11.3, the inverse is not necessarily true: If multilingual students do not meet monolingual norms, this must not be interpreted as an indication of reading difficulty, because multilingual students follow distinct developmental trajectories in their various languages.

When assessing multilingual students, it is crucial to recognize the distinct developmental trajectories that differentiate multilingual Spanish speakers from their monolingual peers, especially in the context of how they learn and use Spanish (Torres and Turner 2017; Bedore et al. 2012; Montrul 2011; Potowski, Jegerski, and Morgan-Short 2009; Gutiérrez–Clellen and Kreiter 2003). For example, multilingual students might use one language predominantly at home and another in professional settings, leading to distinct developmental trajectories that do not fit neatly map onto monolingual speaker norms. More specifically, heritage Spanish speakers learn Spanish at home with the goal of communicating with their family or within their community may have developed less grammatical skills or specialized vocabulary than Spanish speakers who learn in academic settings, instructed in Spanish, and specifically on grammar rules (Potowski, Jegerski, and Morgan-Short 2009; Gutiérrez–Clellen and Kreiter 2003). Multilingual children who acquire Spanish primarily at home often develop strong conversational skills but may lack exposure to more formal versions of the language. This is particularly common among heritage speakers who grow up in Spanish-speaking households but receive most or all of their formal education in English, like many students in the United States who are second-generation immigrants. In contrast, Spanish speakers who learn Spanish through academic settings are likely to have greater exposure to a wider range of vocabulary and complex grammatical structures, which supports their confidence and competence in professional or academic Spanish (Potowski, Jegerski, and Morgan-Short 2009; Gutiérrez–Clellen and Kreiter 2003). As a result, interpreting performance of multilingual speakers solely with comparison to monolingual norms can lead to incorrect assumptions about language proficiency and educational needs. Importantly, such differeneces may not indicate a deficit but rather potentially a different pattern of language development shaped by the unique contexts in which students use Spanish.

11.1 Prevalence

Based on responses to the mandatory Home Language Survey, about 39.5 % (2,310,311) of students enrolled in the California public school system speak a language other than English at home (California Department of Education, 2022). About 19.1 % (1.3 million) of Californian students are classified as English Learners (ELs), meaning that they did not meet the criteria, based on the English Language Proficiency Assessment of California (ELPAC), to be (re)classified as English-proficient. While these students speak more than 100 different languages, 81.9 % are Spanish-speakers, highlighting the need for universal screening instruments in Spanish, such as ROAR-Español. Similar statistics are reflected in other regions of the country such as New York City (NYC) where approximately 43% of students enrolled in NYC public schools speak a primary home language other than English, with ~17% of students in NYC public schools identified as English Language Learners (ELLs). Spanish is by far the most common home language among ELLs in NYC (66%) followed by Chinese (10%).

Importantly, there are complex considerations surrounding EL labels (Umansky and Dumont 2021; Shin 2018; Umansky 2016; Thompson 2015; R. Callahan, Wilkinson, and Muller 2010; R. M. Callahan 2005). While being identified as an EL can provide access to targeted English language development programs, which are designed to support language acquisition and academic success, there is also often stigma associated with the label that parents may take into account when enrolling their children in school (Umansky 2016; R. M. Callahan 2005). Due to this stigma, some parents may choose not to identify their children as ELs or advocate for their reclassification as soon as possible (Umansky 2016; Thompson 2015). This suggests that the reported number of EL students could be lower than the actual number, particularly in communities where there is heightened concern about the negative perceptions associated with the EL label.

11.2 Choosing the Language(s) of Assessment

Determining the appropriate language(s) of assessment for a multilingual student is challenging. Factors to consider are the languages reported to be spoken at home, languages of previous and current instruction, as well as the outcome of interest. Currently, we offer ROAR-English and ROAR-Español as two standalone suites of assessments (Italian, Portuguese, German and French are in development). However, we are continuously exploring ways of combining multilingual students’ scores in multiple languages so that we will be able to provide a unified reading risk estimation for multilingual students.

In the meantime, it is best practice to assess students in all their languages. For Spanish-speaking ELs this means administering both ROAR-English and ROAR-Español and qualitatively interpreting a student’s results in both languages in conjunction with other available information on, for example, their home language environment, current and prior languages of instruction. Multilingual students meeting or exceeding standards derived from monolingual populations may generally be considered as meeting those standards. However, in cases where a multilingual student performs below proficiency thresholds, this may be due to a number of reasons (the ongoing acquisition of the language of assessment, different expected developmental trajectories, etc.) and one should not conclude that this result necessarily indicates risk of reading challenges like dyslexia. For example, consider a second grade student who grew up in a home that primarily spoke Spanish, began learning to speak English when they entered Kindergarten, and was primarily taught to read in English. Their scores on ROAR-English and ROAR-Español would both be useful for gauging their reading development and making planning instruction, but we would not expect their ROAR-Español scores to be at the same level as a monolingual Spanish speaker who is being taught to read in Spanish. ROAR scores provide detailed information about reading skills in each language of assessment but must be interpreted in context alongside other sources of information about the individual student.

11.3 ROAR-Español Scores

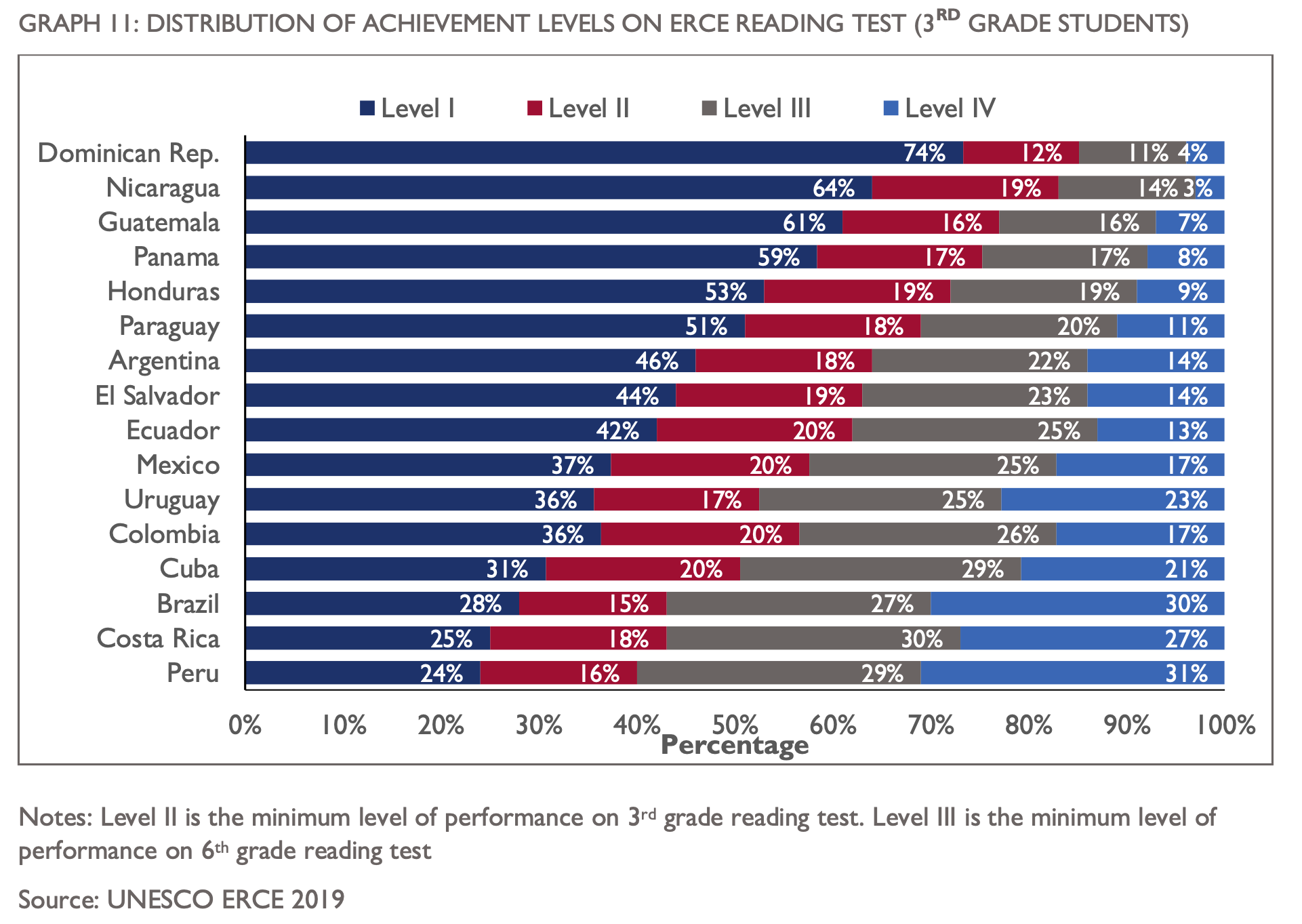

ROAR-Español has been validated in a sample of multilingual learners in California and a sample of (primarily) monolingual Spanish speakers in Colombia (see Bhat et al. (2024) for an initial publication based on ROAR-Español). Care has been taken in the design and validation of each ROAR-Español measure to design the items around the linguistic diversity of Spanish speakers - see the individual introduction sections of each assessment for detailed accounts of the considerations that were taken into account for each. ROAR-Español will return the same types of scores as ROAR-English measures (see Section 3.1 and ROAR Families and Teachers Guide for detailed information) and, additionally, ROAR-Español will return grade level equivalent scores based on the normative data from monolingual Spanish speakers in Colombia. Every country will, of course, have different normative trajectories of reading development. Literacy levels among school-aged children in Colombia is similar to Mexico, but below average compared to other countries in Latin America. Figure 11.1 shows literacy achievement data across different countries in Latin America (reproduced from (Zambrano et al. 2022)). The large, urban, school districts we partnered with in Colombia perform above that national average and could be considered reasonably representative of a typical learning trajectory for a (primarily) monolingual Spanish speaker in an urban area of Latin America. Moreover, the representative data we collected in California schools places Spanish speaking students from California within the typical range of the Colombian norms. Thus, ROAR-Español Grade Level Equivalent (GLE) Scores can provide useful information to teachers in the United States about a student’s Spanish reading proficiency relative to monolingual learners in Latin America. These data can be useful for interpreting scores on an English screener. For example, a new second grade student who has just moved from a monolingual Spanish environment to the U.S. who has low scores on ROAR measures in English but with GLE Scores on ROAR-Español that are in the typical range for a second grader still needs additional reading instruction, but is not at high risk for dyslexia as their scores suggest their trajectory of foundational reading skills in Spanish are on track.

11.4 Vignettes: Interpretation and Use of Multilingual Students’ Scores

11.4.1 Vignette 1

A student who grew up and attended (pre-)school in Mexico arrives in the U.S. with their family in the summer before starting second grade. The family reports speaking Spanish at home and that their child had attended two years of prior instruction in Spanish. In this case, knowing how this student fares in relation to his monolingual Spanish peers is of value, as this is a fair comparison–the student has, hitherto, lived in a linguistic environment and had a scholastic experience that is represented by the largely monolingual Colombian norming sample (as Colombia and Mexico also have comparable literacy achievement levels. See Figure 11.1). This student, having attended school in Mexico with primary instruction in Spanish, will not have had many opportunities to learn English. In this case, even if the student is deemed to have met the minimal requirements to be assessed in English, their performance on any English assessment is not particularly meaningful, as it will be a function of their lacking exposure to the English language, rather than of any underlying reading difficulty.

Thus, if this student’s English scores suggest that they are in need of additional support, this result should not be interpreted in isolation. Rather, one ought to obtain the student’s ROAR-Español scores to better understand the support they might need. If the student’s ROAR-Español grade level equivalent score classifies them as performing at grade-level/on-track, then one can conclude that the student is likely not at risk of developing a reading difficulty/dyslexia. They will need support in translating their Spanish reading skills to English since English is a highly irregular writing system (i.e., an opaque orthography). But needing instruction is qualitatively different than being at risk for long-term reading difficulties like dyslexia. If the student’s ROAR-Español grade level equivalent score results in a ‘needing support’/not-on-track classification, further assessment is recommended.

11.4.2 Vignette 2

An incoming first-grade student grows up in a predominantly Spanish-speaking family in California. While the students parents were born in Mexico and had moved to the U.S. in their adult life, the student was born in the U.S., lived in a linguistically diverse neighborhood where both English and Spanish are spoken, and attended pre-school and kindergarten classes where English was the language of instruction. In this case, though the student only hears and speaks Spanish at home, their instructional experience and formal language instruction was exclusively English.

Here, we cannot reasonably expect the student to perform similarly to monolingual Spanish speakers on the ROAR-Español because their linguistic and educational experiences were spread out across multiple languages. Therefore, their grade level equivalent score is much less meaningful and no “risk” classification should be made on the basis of their Spanish performance, alone. At the same time, the students cannot be fairly compared to monolingual English speakers on English assessments as their experiences learning English are not comparable. Ultimately, testing in both languages is strongly recommended and, due to multilingual individuals heterogeneity and distinct developmental trajectories, the student’s performance is best judged in conjunction with other qualitative information available. The important metric for this student will be their growth over time and schools should carefully monitor their learning trajetory. This vignette serves to highlight the challenges in assessment of multilingual learners. Even though the goal of screening is often to produce a simple and interpretable “risk metric”, interpreting assessment data in multilingual learners requires nuance and expertise and should always take into account the learning context of the individual being assessed.