6 Sentence Reading Efficiency (ROAR-Sentence)

ROAR-Sentence measures the speed or efficiency with which participants can read sentences for understanding. Being able to efficiently read connected text for understanding is at the foundation of reading development and is a major bottle-neck for children with dyslexia. ROAR-Sentence is specifically designed to tap into reading efficiency and sentences are syntactically and semantically simple, avoid low frequency words and complex sentence structures, and have unambiguous answers that require little, if any, background knowledge.

As reading skills develop, the speed with which children can read connected text becomes particularly important (Silverman, Speece, and Harring 2013). “Efficient word recognition” was highlighted in the original conceptualization of the “simple view of reading” (Hoover and Gough 1990), and fluent reading has been implicated as a bridge between decoding skills and reading comprehension (Pikulski and Chard 2005; Silverman, Speece, and Harring 2013). Children with dyslexia and other word reading difficulties often struggle to achieve fluency, and struggles with word reading speed and fluency have always been core to the definition of dyslexia (Catts et al. 2024; Lyon, Shaywitz, and Shaywitz 2003). Yeatman et al. (2024) provide a detailed description of the development of a silent sentence reading efficiency (SRE) measure that was designed to be fast, reliable, efficient at scale, and targeted to the issues with speed/fluency that present a bottleneck for so many struggling readers. We provide key details here in the technical manual (using much of the same text) and refer readers to the peer-reviewed publication for more details of the research and development process (Yeatman et al. 2024).

6.1 Defining the construct of Sentence Reading Efficiency

Timed reading measures go under a variety of names (e.g., reading fluency, reading efficiency, etc) and involve different levels of demands on comprehension and articulation, making it hard to interpret the extent to which scores reflect differences in reading efficiency versus separate constructs. We designed ROAR-Sentence to isolate reading efficiency by minimizing comprehension demands while maintaining checks for understanding, and we used a silent reading task to a) avoid the confounds of articulation that are inherent to oral reading tasks and b), measure the most ecologically valid form of reading (silent reading). This stands in contrast to other reading fluency measures that confound articulation, comprehension and efficiency leading to a less interpretable score.

6.2 Other measures of oral and silent reading efficiency and fluency

Traditional measures that are most similar to ROAR-SRE are sometimes referred to as sentence reading fluency tasks, and while they are not administered online, they do elicit silent responses from students. For example, the Woodcock Johnson (WJ) Tests of Achievement “Sentence Reading Fluency” subtest (Schrank et al. 2014), and Test Of Silent Reading Efficiency and Comprehension (TOSREC) (Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C. A., & Pearson, N. A. 2010), rely on an established design: A student reads a set of sentences and endorses whether each sentence is true or false. For example, the sentence, Fire is hot, would be endorsed as True. A student endorses as many sentences as they can within a fixed time limit (usually three minutes). The final score is the total number of correctly endorsed sentences minus the total number of incorrectly endorsed sentences. Both the WJ and TOSREC are standardized to be administered in a one-on-one setting (though TOSREC can also be group administered) and the stimuli consist of printed lists of sentences which students read silently and mark True/False with a pencil. Even though the criteria for item development on these assessments is not specified in detail, there is a growing literature showing the utility of this general approach. First of all, this quick, 3 minute assessment is straightforward to administer and score and has exceptional reliability, generally between 0.85 and 0.90 for alternate form reliability (Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C. A., & Pearson, N. A. 2010; Johnson, Pool, and Carter 2011; Wagner 2011). Moreover, this measure has been shown to be useful for predicting performance on state reading assessments: For example, Johnson and colleagues demonstrated that TOSREC scores could accurately predict students who did not achieve grade-level performance benchmarks on end-of-the-year state testing of reading proficiency (Johnson, Pool, and Carter 2011).

Further evidence for validity comes from the strong correspondence between silent sentence reading measures such as the TOSREC and Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) measures (Denton et al. 2011; Wagner 2011; Johnson, Pool, and Carter 2011; Kang and Shin 2019; Y.-S. Kim, Wagner, and Lopez 2012; Y.-S. G. Kim, Park, and Wagner 2014; Price, Meisinger, and Louwerse 2016). ORF is one of the most widely used measures of reading development in research and practice, and some have even argued for ORF as an indicator of overall reading competence (Fuchs, Fuchs, and Hosp 2001). ORF is widely used to chart reading progress in the classroom, providing scores with units of words per minute that can be examined longitudinally (e.g., for progress monitoring (Cummings, Park, and Bauer Schaper 2013; Good, Gruba, and Kaminski 2002; Hoffman, Jenkins, and Dunlap 2009)), compared across classrooms and districts, and can inform policy decisions such as how to confront learning loss from the Covid-19 pandemic (Domingue et al. 2021, 2022). Even though silent reading and ORF are highly correlated, the measures also have unique variance (Hudson et al. 2008; Y.-S. Kim, Wagner, and Lopez 2012; Wagner 2011) and, theoretically, have different strengths and weaknesses. For example, even though there are strong empirical connections between ORF and reading comprehension (Y.-S. G. Kim, Park, and Wagner 2014), ORF does not require any understanding of the text and has been labeled by some as “barking at print” (Samuels 2007). Silent reading, on the other hand, is the most common form of reading, particularly as children advance in reading instruction. In line with this theoretical perspective, Kim and colleagues found that silent sentence reading fluency was a better predictor of reading comprehension than ORF starting in second grade (Y.-S. Kim, Wagner, and Lopez 2012). Thus, given the practical benefits of silent reading measures (easy to administer and score at scale), along with the strong empirical evidence of reliability, concurrent, and predictive validity, and face validity of the measure, an online measure of silent sentence reading efficiency would be useful for both research and practice.

6.3 Structure of the task and design of the items

ROAR-Sentence uses a similar task design as the Test of Silent Reading Efficiency and Comprehension (TOSREC) and WJ Sentence Reading Fluency sub-test with the major differences being: a) ROAR-Sentence is a gamified online task rather than pencil and paper and b) the ROAR-Sentence items are designed specifically to tap into silent sentence reading efficiency. Figure 6.1 shows the ROAR-Sentence task.

The strength of silent reading fluency/efficiency tasks is also their weakness: On the one hand, these tasks include comprehension, which bolsters the argument for the face validity of silent reading measures. On the other hand, what is meant by comprehension in these sentence reading tasks is often ill-defined and, thus, a low score lacks clarity on whether the student is struggling due to difficulties with “comprehension” or “efficiency”. As a concrete example, sentences in the TOSREC incorporate low frequency vocabulary words (e.g., porpoise, bagpipes, locomotive, greyhounds, buzzards) meaning that vocabulary knowledge as well as specific content knowledge (e.g., knowledge about porpoises, bagpipes and locomotives) will affect scores. While this design decision might be a strength in some scenarios (e.g., generalizability to more complex reading measures such as state testing), it presents a challenge for interpretability. An interpretable construct is critical if scores are used to individualize instruction. For example, does a fourth grade student with a low TOSREC score need targeted instruction and practice focused on a) building greater automaticity and efficiency in reading or b) vocabulary, syntax and background knowledge. Our goal in designing a new silent sentence reading efficiency measure was to more directly target reading efficiency by designing simple sentences that are unambiguously true or false and have minimal requirements in terms of vocabulary, syntax and background knowledge. Ideally, this measure could be used to track reading rate in units of words per minute, akin to a silent reading version of the ORF task, but with a check to ensure reading for understanding.

To consider the ideal characteristics of these sentences, it may be helpful to begin by considering the ORF task which is used to compute an oral reading rate (words per minute) for connected text. In an ORF task, the test administrator can simply count the number of words read correctly to assess each student’s reading rate. Translating this task to a silent task that can be administered at scale online poses an issue because an administrator is unable to monitor the number of sentences read by the student. A student could be instructed to press a button on the keyboard after the completion of a sentence in order to proceed to the next one. However, the validity of this method depends on the student’s ability to exhibit restraint and wait until the completion of each sentence before proceeding to the next sentence.

In the interest of preserving the validity of the interpretations of the scores, we retain the True/False endorsement of the TOSREC and WJ, but reframe its use. That is, for the ROAR-Sentence task, the endorsement of True/False should be interpreted as an indication that the student has read the sentence, rather than as an evaluation of comprehension per se. In this context, if the student has difficulty comprehending a sentence, or if the student takes a long time to consider the correct answer because the sentence is confusing, syntactically complex, or depends on background knowledge and high-level reasoning, we lose confidence in the inferences that we can make about a student’s reading efficiency. As such, it is important that sentences designed for this task are simple assertions that are unambiguously true or false. However, creating sentences to adhere to these basic standards may not always be straightforward. For example, the statement “the sky is blue” may be true for a student in the high-plain desert in Colorado but may be a controversial statement for a student in Seattle. Thus, careful consideration must be given to crafting sentences that do not depend on specific background knowledge and are aligned with the goal of measuring reading efficiency. (Yeatman et al. 2024) provides a detailed description of the iterative research and design process that went into defining and validating this construct and the reader is referred to that publication for more details on the item bank.

6.4 Scoring

ROAR-Sentence is a two alternative forced choice (2AFC) task and is scored as the total number of correct responses minus the total number of incorrect responses in the alloted (3 minute) time window. This scoring method controls for guessing by controlling for the number of incorrect responses in the calculation of the scores.

Types of Scores

- Raw Scores: The student’s raw score will range between 0-130.

- Percentile Scores: Percentile scores are computed in 2 ways (see Chapter 3):

- Based on ROAR Norms

- Based on linking ROAR scores to Test of Silent Reading Efficiency and Comprehension (TOSREC) and Woodcock Johnson Sentence Reading Fluency Standard Scores. This linking allows ROAR-Sentence scores to be interpreted with direct reference to the criterion measure that is often used to define dyslexia risk.

- Standard Scores: Age standardized scores for ROAR-Sentence put scores for each age bin on a standard scale (normal distribution, \(\mu=100\), \(\sigma=15\)) and are computed in 2 ways:

- Based on ROAR Norms

- Based on linking ROAR scores to TOSREC and WJ Standard Scores.

6.5 Norms

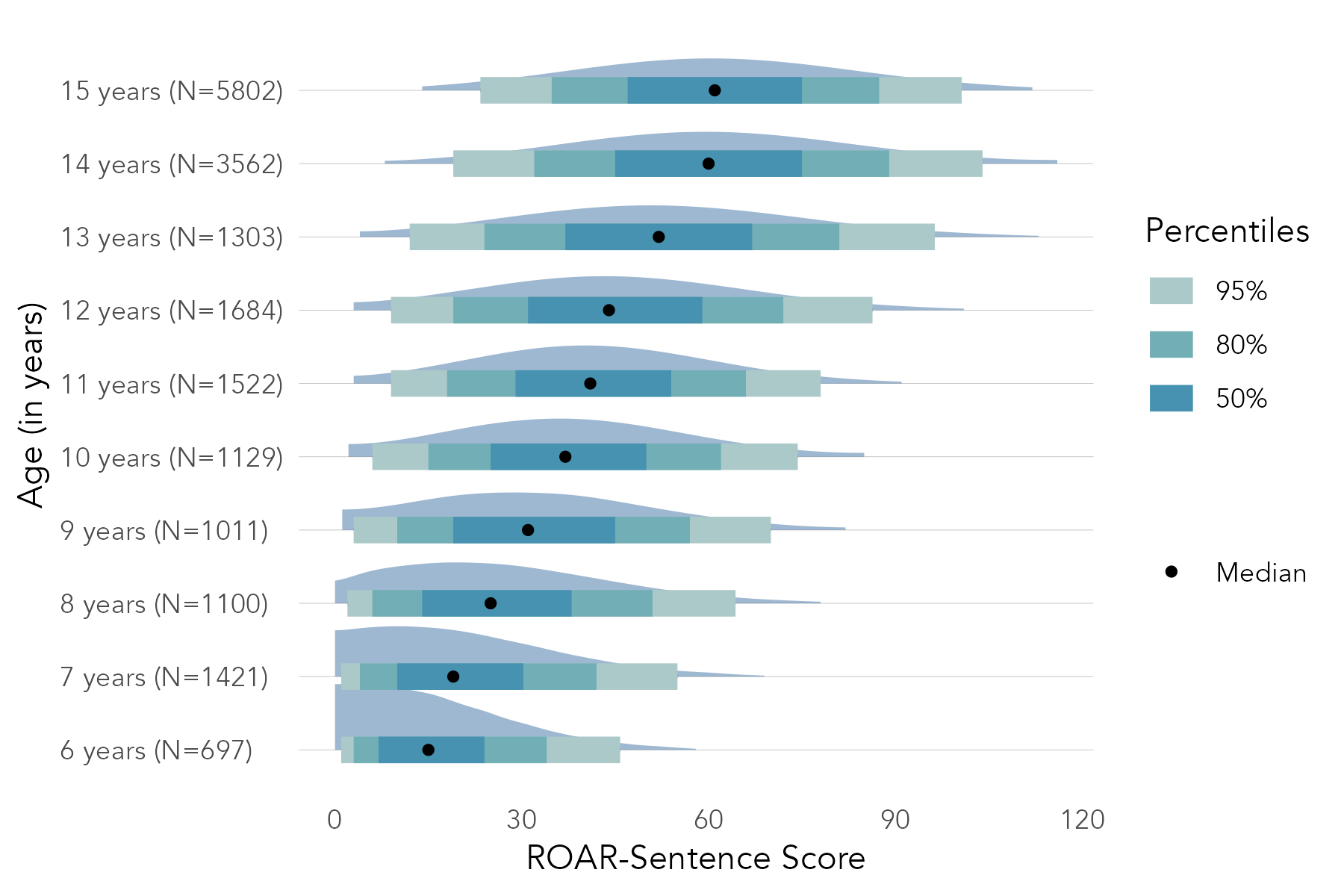

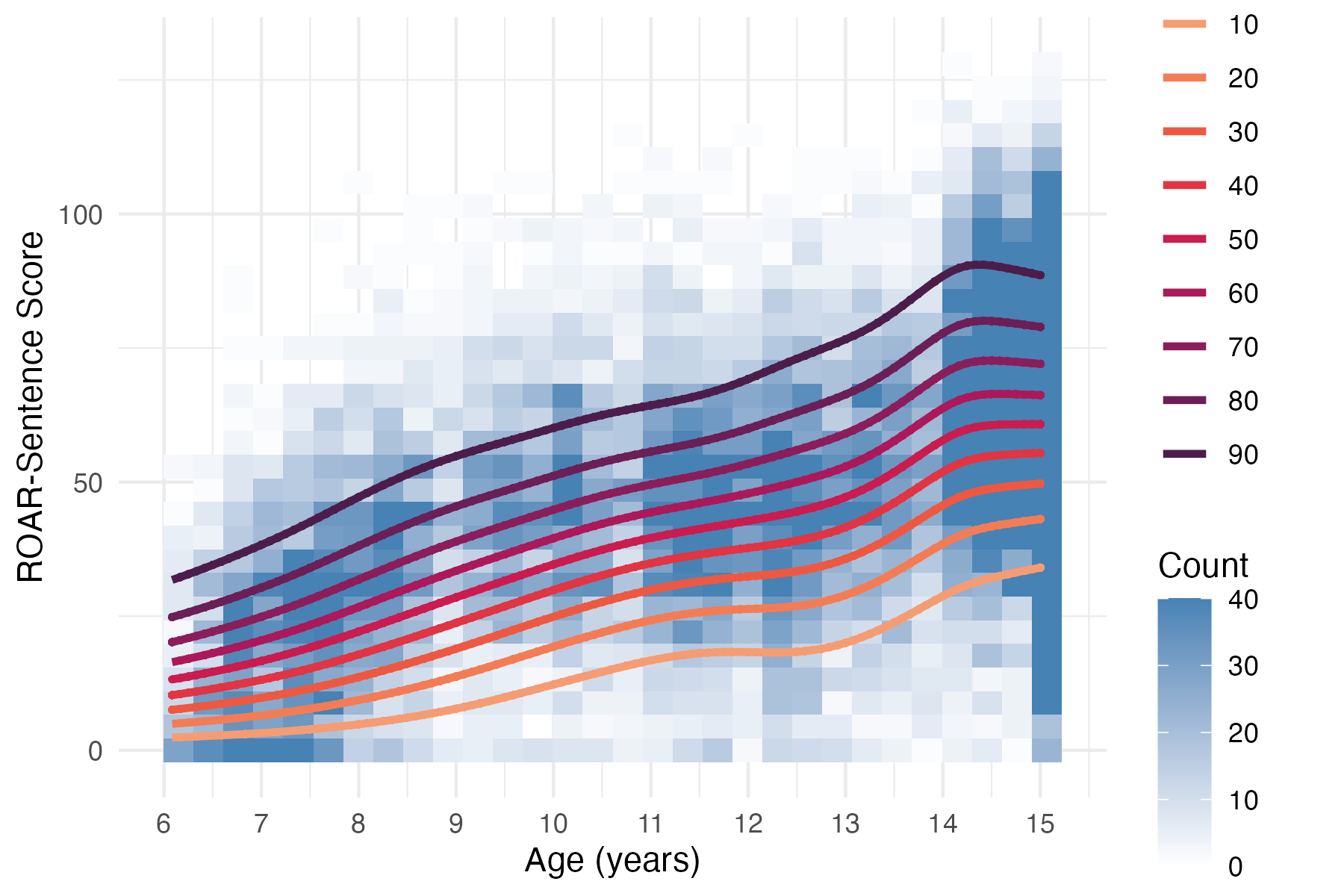

Section 3.4 describes the norming model used for ROAR-Sentence (and the Foundational Reading Skills Suite). Figure 6.2 shows the normative progression of ROAR-Sentence Scores as a function of age and Figure 6.3 shows percentile curves fit to ROAR-Sentence Scores.

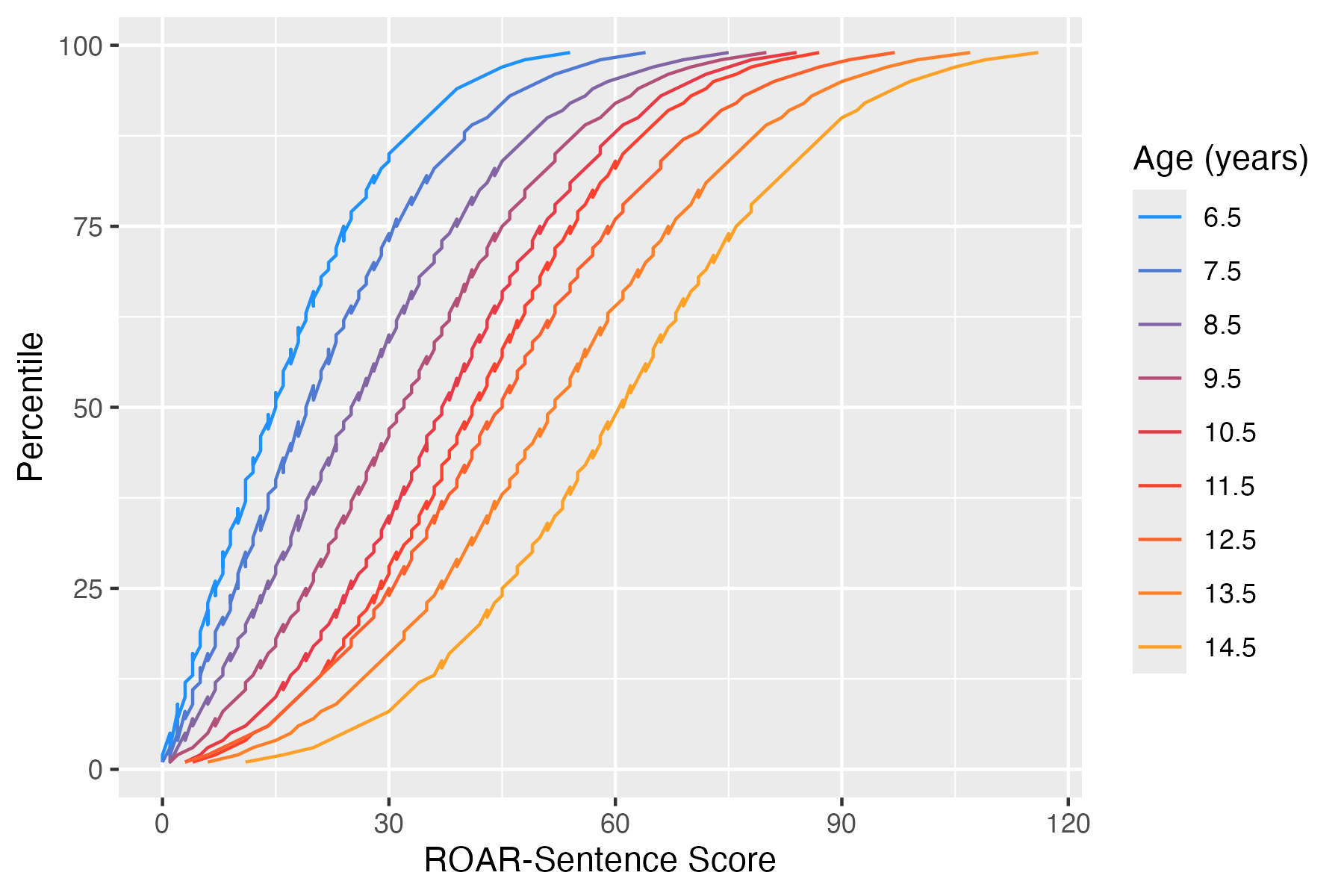

Based on this norming model, Percentile Scores are derived for each age. Figure 6.4 shows the relationship between ROAR-Sentence Scores and Percentile Scores.