| Overall (N=1143) |

|

|---|---|

| Grade | |

| 6 | 264 (23.1%) |

| 7 | 166 (14.5%) |

| 8 | 236 (20.6%) |

| 10 | 477 (41.7%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black or African American | 176 (15.4%) |

| N/A | 2 (0.2%) |

| Asian | 24 (2.1%) |

| Hispanic | 802 (70.2%) |

| Multiracial | 38 (3.3%) |

| White | 101 (8.8%) |

| ELL Status | |

| No | 1048 (91.7%) |

| Yes | 95 (8.3%) |

| Special Education Status | |

| No | 905 (79.2%) |

| Yes | 238 (20.8%) |

| Primary Language | |

| English | 819 (71.7%) |

| Other | 66 (5.8%) |

| Spanish | 258 (22.6%) |

| Free or Reduced Lunch | |

| No | 193 (16.9%) |

| Yes | 950 (83.1%) |

33 Prediction of Comprehension and Summative Assessment

Even though foundational reading skills are not the focus of middle school and high school education, they remain a barrier for many students. For a middle or high school student who has not yet mastered decoding skills, every class is likely to be a struggle. Moreover, comprehension will be a challenge for a student who is still struggling to read efficiently and fluently. ROAR-Word (Chapter 5) and ROAR-Sentence (Chapter 6) provide valuable screening information in middle school and high school and can highlight an actionable bottleneck to learning. Table 24.3 presents concurrent validity data showing that ROAR-Word is a valid measure of single word reading ability from kindergarten through high school, Chapter 16 demonstrates that ROAR-Word is reliable through high school, and Chapter 17 demonstrates that ROAR-Sentence is reliable through high school. Thus, the technical properties of the ROAR Foundational Reading Skills Suite (Section 2.1) suggest utility across the grades. Here we focus on prediction of reading comprehension and scores on state summative assessments to validate the utility of the ROAR Foundational Reading Skills Suite for screening challenges that impact performance across academic domains in older students.

33.1 Recommended uses of ROAR Foundational Reading Skills in Middle/High School

Decoding and fluency remain critical foundational skills in middle and high school, essential for comprehending complex texts across all subjects. Wang et al. (2019) highlight a “Decoding Threshold,” demonstrating that students below a certain proficiency level often experience stagnant comprehension growth as they struggle with basic word recognition. Crucially, foundational reading skills are actionable; effective interventions to help older students improve their decoding and fluency are well established (Reed 2010; Vaughn et al. 2008; Lovett et al. 2021). What Works Clearinghouse has synthesized the research based on Providing Reading Interventions for Students in Grades 4-9 and published a comprehensive practice guide (Vaughn et al. 2022). Providing this targeted support can enable students to cross the threshold and unlock widespread academic improvement by freeing cognitive resources to focus on meaning.

ROAR Foundational Reading Skills Suite is an efficient way to screen for challenges in decoding and reading efficiency that might be a bottleneck for learning across domains. We recommend using these two measures as a universal screener, interpreting ROAR screening data alongside measures of comprehension, and triaging students into the most effective intervention to target their specific challenges.

33.2 Study 1: Predictive Validity - High-Stakes Summative Assessments

Every state conducts end-of-year assessments with a shared overarching goal to provide a summative measure of student learning against established standards at the close of the academic year. Assessments such as SBAC (Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium) and MCAS (Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System) serve as summative evaluations, providing a comprehensive snapshot of student learning and mastery of state standards in core subjects at the culmination of an academic year. The results of these assessments often carry significant weight, making them high-stakes. They are frequently used to inform school accountability measures, identify schools needing support, and evaluate the effectiveness of educational programs, thus impacting funding and interventions within the state’s educational system. This comprehensive evaluation allows each state to gauge the overall effectiveness of its educational system, identify areas of strength and weakness in curriculum and instruction, and track progress in closing achievement gaps among student populations. Ultimately, these assessments aim to inform data-driven decisions for continuous improvement in teaching and learning, ensuring a more equitable and effective education for all students within their respective public school systems. Improving scores on high-stakes assessments is challenging because they encompass so many aspects of learning. We ran a series of studies to investigate the likelihood that challenges in foundational reading skills are a major factor for students who are not meeting expectations in terms of state standards.

Table 33.1 shows the demographics of middle and high school students who completed ROAR-Word and ROAR-Sentence during the Fall and then completed the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) at the end of the year (Spring).

33.2.1 Prediction of MCAS Classifications

Like many high-stakes summative assessments, MCAS is used to classify students based on whether or not they are meeting expectations based on state standards. We next ask whether challenges with Foundational Reading Skills might explain why many students are not meeting expectations on MCAS. Table 33.2 shows the distribution of MCAS achievement levels as defined by state standards.

| Grade | MCAS Proficiency Level | N | Proportion of Proficiency Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Exceeding Expectations | 5 | 1% |

| 6 | Meeting Expectations | 46 | 17% |

| 6 | Partially Meeting Expectations | 126 | 48% |

| 6 | Not Meeting Expectations | 89 | 34% |

| 7 | Exceeding Expectations | 5 | 2% |

| 7 | Meeting Expectations | 14 | 8% |

| 7 | Partially Meeting Expectations | 94 | 57% |

| 7 | Not Meeting Expectations | 55 | 33% |

| 8 | Exceeding Expectations | 5 | 2% |

| 8 | Meeting Expectations | 42 | 18% |

| 8 | Partially Meeting Expectations | 120 | 51% |

| 8 | Not Meeting Expectations | 69 | 29% |

| 10 | Exceeding Expectations | 24 | 5% |

| 10 | Meeting Expectations | 149 | 31% |

| 10 | Partially Meeting Expectations | 223 | 47% |

| 10 | Not Meeting Expectations | 81 | 17% |

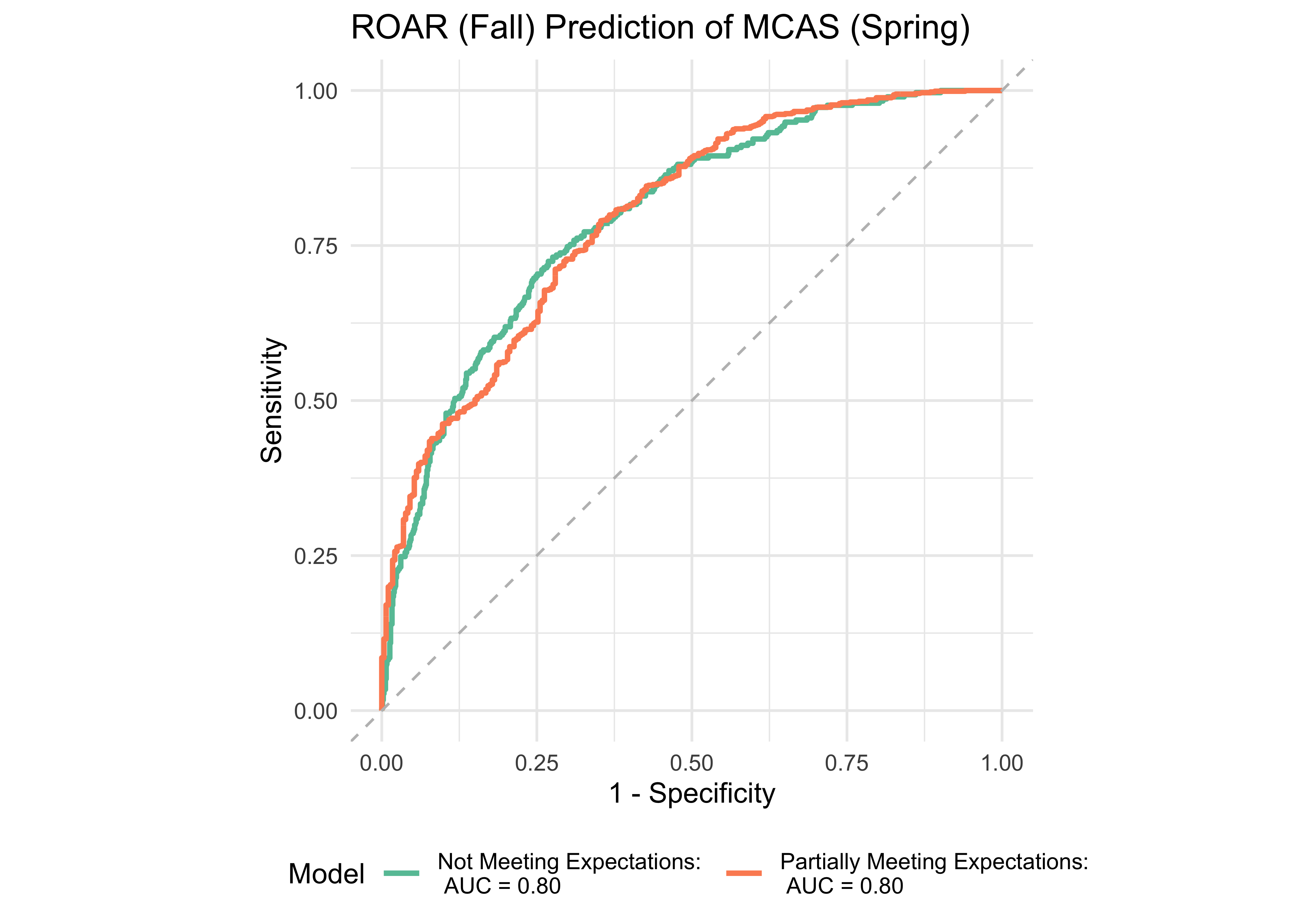

A generalized additive model (GAM) with a logistic link function was used to predict MCAS classifications based on ROAR Foundational Reading Skills measured in the Fall. The classification model included ROAR-Word, ROAR-Sentence and Grade. Figure 33.1 shows ROC curves demonstrating an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.8 for predicting students who will be classified as “Partially Meeting Expectations” or “Not Meeting Expectations”. Prediction accuracy was 81.4% for “Partially Meeting Expectations” or “Not Meeting Expectations” and 79.2% for “Not Meeting Expectations”.

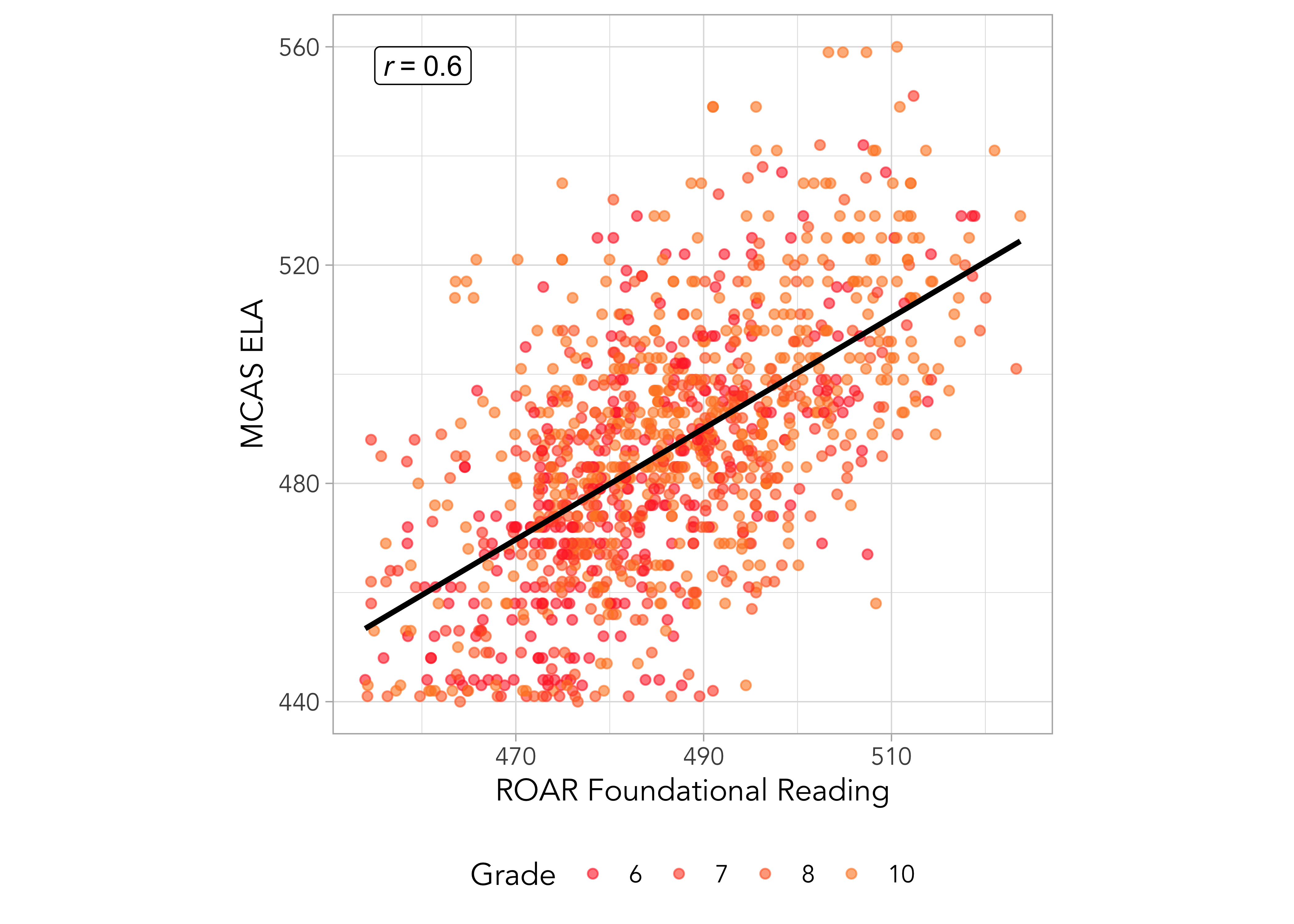

33.2.2 Prediction of MCAS Scores

Beyond classifications, MCAS also provides a continuous measure of student performance. Figure 33.2 shows the prediction of end of the year MCAS scores based on ROAR Foundational Reading Skills (ROAR-Word + ROAR-Sentence) completed in the Fall and Table 33.3 shows the breakdown by grade. Foundational Reading Skills account for a substantial amount of the variation in MCAS performance indicating that many students are likely struggling on summative assessment due to challenges with decoding and reading fluency.

The predictive relationship between Fall ROAR scores and end of the year summative test scores is consistent across middle school and high school as seen in Table 33.3.

| Grade | ROAR Composite | ROAR-Word | ROAR-Sentence | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 1143 |

| 6 | 0.66 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 264 |

| 7 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 166 |

| 8 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 236 |

| 10 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 477 |

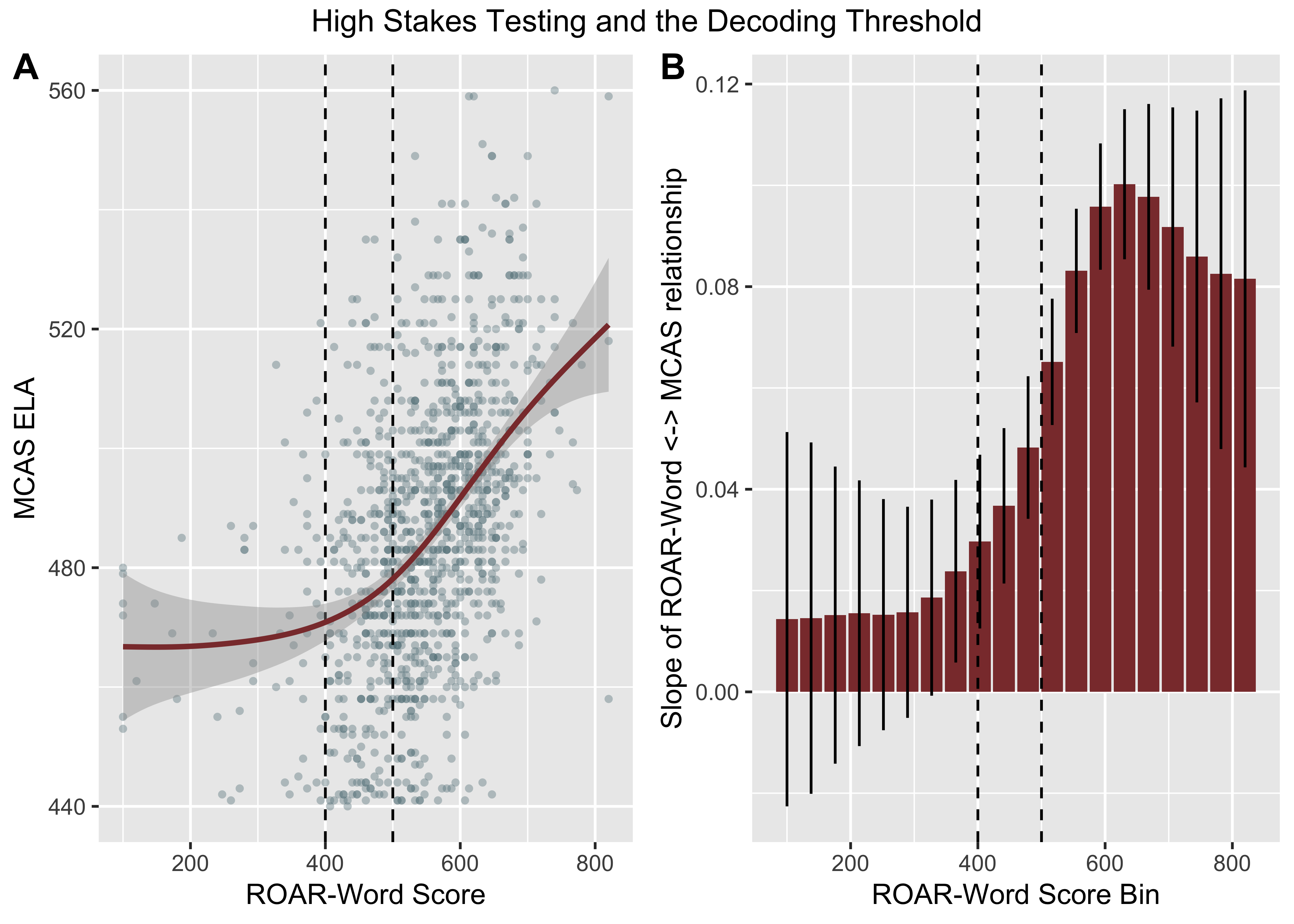

33.2.3 Decoding Threshold

The “Decoding Threshold Hypothesis” proposes that decoding and comprehension are tightly linked after students surpass a certain threshold in decoding skills (Wang et al. 2019). Figure 33.3 shows the relationship between ROAR-Word and MCAS scores. Below a threshold of 400 or 500 on ROAR-Word, the relationship to MCAS flattens out as predicted by the Decoding Threshold Hypothesis. Chapter 34 demonstrates that the decoding threshold can also be seen by analyzing the relationship between sentence reading efficiency and single word reading.

A ROAR-Word score of 400 is the 50th percentile for an 8-year-old, a score of 450 is the 50th percentile for a 9-year-old, and a score of 500 is the 50th percentile for a 10-year-old. Thus, the Decoding Threshold corresponds to the average single word reading skills in 3rd-5th grade, a developmental window which makes sense with respect to the broader literature on decoding and comprehension in older students (see Section 33.4.1).

Based on national norms, a school should expect about 23% of their graduating 8th graders / incoming 9th graders to be a score of 500, 13% below a score of 450, and 7% below a score of 400. Another way to think of these numbers is that they are estimates of the percentage of middle/high school students that still need support in foundational reading skills like decoding.

33.2.4 Study 1 Conclusions

Many students who are not meeting the expectations set by state standards have not yet established strong foundational reading skills. Even though this type of predictive validity study cannot establish causality (Frank et al. 2025), it is reasonable to assume the difficulties with decoding and reading efficiency are a major contributor to the struggles faced by many middle and high school students. Moreover, we find evidence that the Decoding Threshold affects performance on summative assessments. Chapter 34 presents additional evidence that ROAR-Word is sensitive to the Decoding Threshold (Wang et al. 2019) in middle school and high school. Using ROAR as a screener to triage students into targeted interventions for foundational reading skills could be an effective policy to improve performance on state tests.

33.3 Study 2: ROAR and iReady

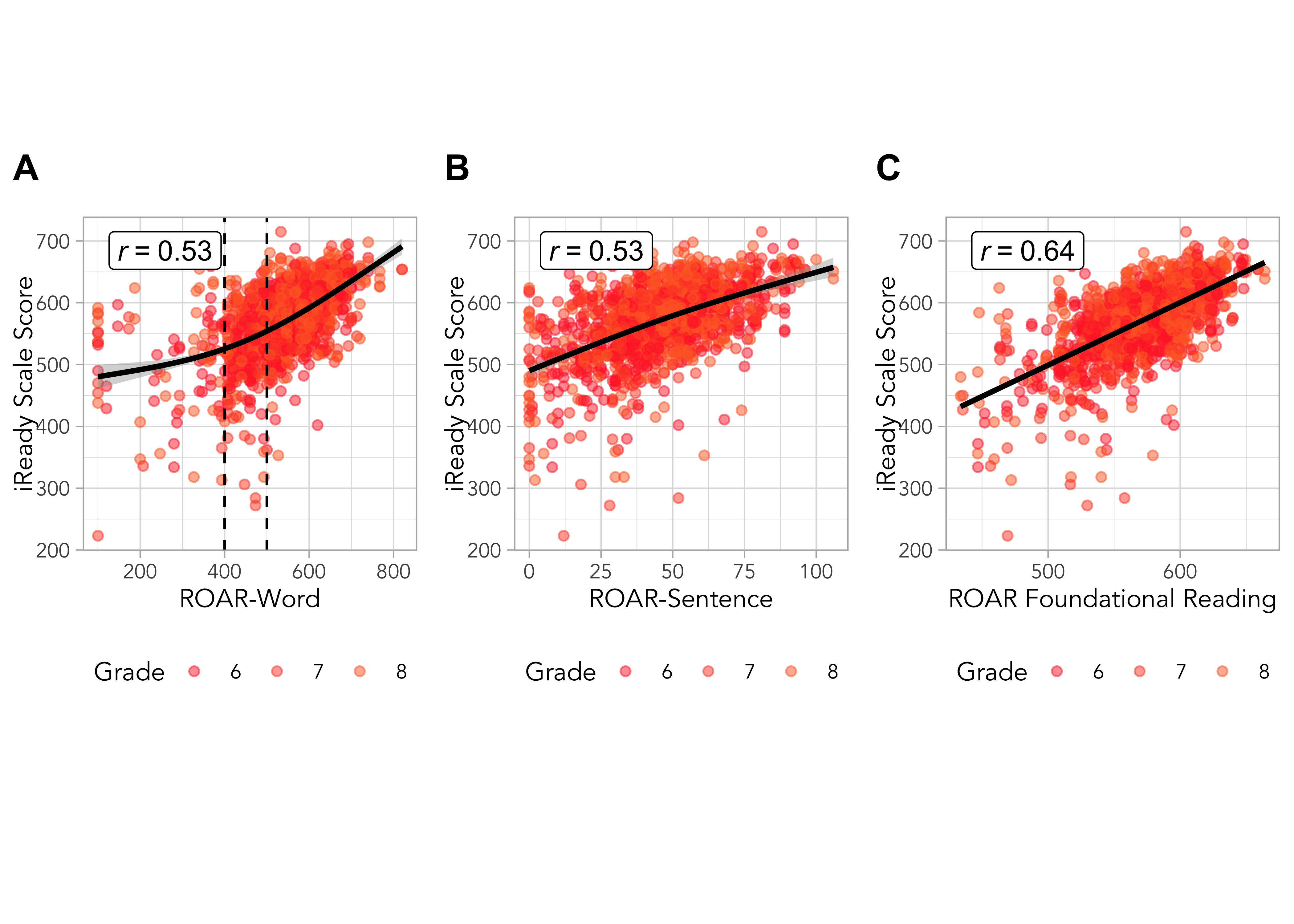

33.3.1 Prediction of iReady Scaled Scores

Beyond state testing, schools use many different assessments of comprehension skills. iReady is another widely used measure of reading comprehension in middle school. Study 2 involved 1333 middle school students who completed iReady and ROAR Foundational Reading Skills in the Fall (overlapping sample with Section 33.2, see Table 33.1). Figure 33.4 shows the predictive relationship between ROAR-Word, ROAR-Sentence, and iReady Scaled Scores. Combining ROAR-Word and ROAR-Sentence to predict iReady Scaled Scores based on a GAM revealed a similar predictive relationship as between ROAR and MCAS (see Figure 33.4 Panel C, r = 0.64). Moreover each individual measure was correlated with iReady (r > 0.5). Examining the relationship between ROAR-Word and iReady, once again, reveals the Decoding Threshold (dashed line in Figure 33.4 Panel A).

33.3.2 Study 2 Conclusions

iReady is a reading comprehension assessment that is aligned to common core standards. It is widely used in the upper grades. Study 2 examined reading comprehension in 1333 middle school students and replicated a) the predictive relationship between ROAR Foundational Reading Skills and comprehension and b) the Decoding Threshold.

33.4 Summary of the Broader Literature on Decoding and Fluency in Older Students

The following sections provide an overview of the literature on decoding, fluency, comprehension, and performance of state tests in middle school and high school. We take a historical perspective with the goal of understanding the reasons that challenges with foundational reading skills are often overlooked in older students.

33.4.1 Historical Perspectives on Assessment of Older Students

For your average high school student, decoding plays a lesser role than vocabulary, reasoning skills, and background knowledge in predicting comprehension. For example Schatschneider et al. (2004) found that while oral reading fluency (ORF) is the dominant predictor of reading comprehension scores in third grade (as measured by the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test; FCAT), verbal knowledge and reasoning skills become the dominant predictors by tenth grade (see FCRR Technical Report #5 and FCRR Technical Report #6). This highlights a significant developmental shift. Jenkins and Jewell (1993) found that the correlation between ORF and comprehension (as measured by the Gates-MacGinitie) declined from r=0.83 in second grade to r=0.67 in 6th grade (r=0.88 in 3rd; r=0.86 in 4th; r=0.73 in 5th). Jenkins and Jewell (1993) reported a similar pattern for the Metropolitan Achievement Test (MAT-6): r=0.87 in 2nd, r=0.70 in 3rd, r=0.79 in 4th, r=0.68 in 5th, and r=0.60 in 6th grade. The demonstration of a developmental shift where decoding and fluency become less important for your average middle/high school student have often been interpreted to indicate that foundational reading skills are no longer relevant to comprehension for older students. However, an alternative interpretation is that the average student in grades 6 and above has already mastered decoding and, for those students with a strong foundation, decoding is no longer the bottleneck for comprehension. Under this interpretation, there are still many students for whom foundational skills remain the bottleneck. In line with this interpretation, the effect sizes for fluency and decoding in predicting comprehension remain significant and meaningful (e.g., r=0.60 in Jenkins and Jewell (1993) and Table 33.3 for ROAR Foundational Reading Skills). These findings highlight the critical importance of continuing to screen for reading difficulties in the upper grades.

33.4.2 Emerging Perspectives on the Importance of Foundational Reading Skills in Older Students

Others beyond (Wang et al. 2019) have highlighted the important role of foundational reading skills in older students. For example White et al. (2021) report results from the 2018 NAEP Oral Reading Fluency Study which examined the relationship between (1) Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) measured by timed passage reading, (2) Real Word and Pseudo Word list reading, and (3) Reading Comprehension measured by the NAEP in fourth grade. They found that those in the advanced group had almost double the pseudoword reading rate as those in the below basic group and, more broadly, that many students in the lowest achievement levels had profound struggles with foundational reading skills. Even though the study did not include ORF measures in the 8th or 12th grade samples, it is likely that the results would be similar since intervention/instruction in foundational reading skills is not common in the older grades.

“The 2018 ORF study reveals that for an estimated 1.27 million fourth-grade public school students performing below NAEP Basic, and particularly for an estimated 0.42 million fourth-grade students in the below NAEP Basic Low subgroup, fluent reading of connected text—sufficiently fast and accurate reading of sentences and passages—can be a major challenge. The study also shows that word reading and phonological decoding skills are underdeveloped in students performing below NAEP Basic, particularly for students in the below NAEP Basic Low subgroup (White et al. 2021, 13).”

Denton et al. (2011) examined the predictive relationship between oral reading fluency, silent reading fluency, and performance on summative assessments (Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills Scale Score; TAKS) in a sample of 1,421 6-8th grade students in Texas. They found moderate correlations between silent reading tasks and state tests (r=0.56 between TOSREC and TAKS; r=0.40 between AIMSweb Maze and TAKS) and slightly lower correlations for ORF (r=0.36-0.50). Another study by Cirino et al. (2013) of 1,748 6-8th grade students that oversampled struggling readers found a high prevalence in decoding and fluency challenges in the 1,025 struggling readers. Thus, even though it isn’t common to assess foundational reading skills in middle school and high school, there is mounting evidence that many older students are still struggling to master decoding and fluency and that these challenges are likely contributing factors to broader academic struggles.